Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

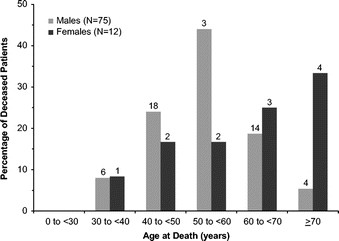

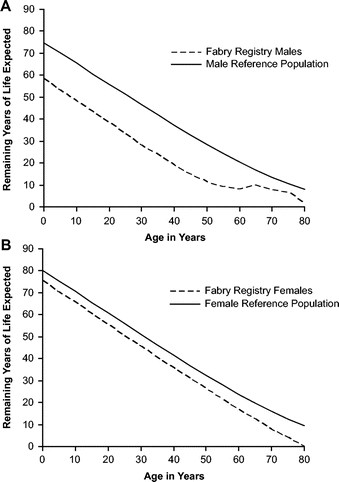

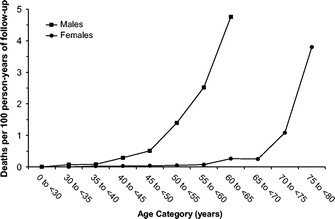

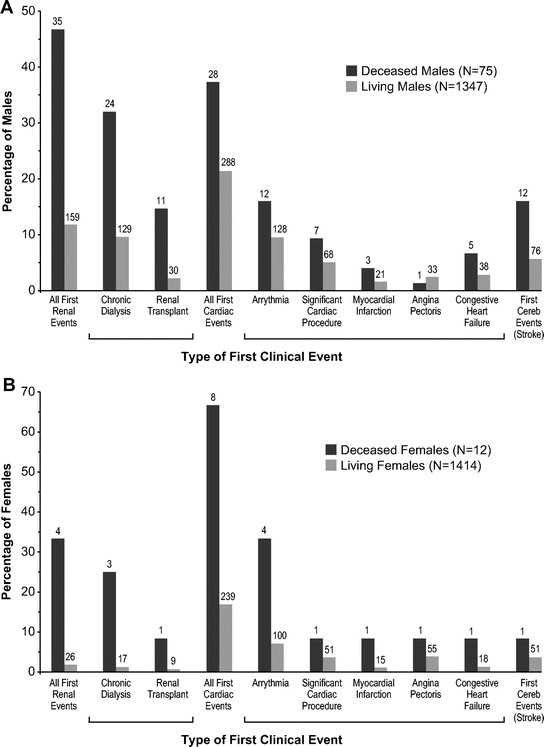

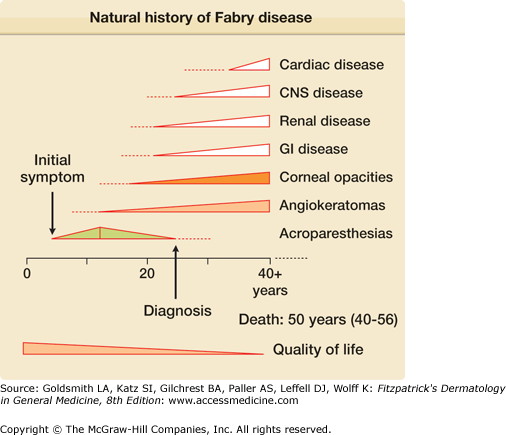

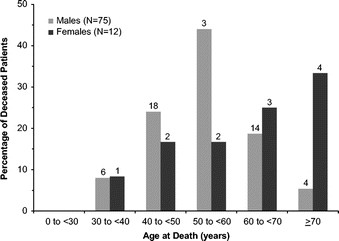

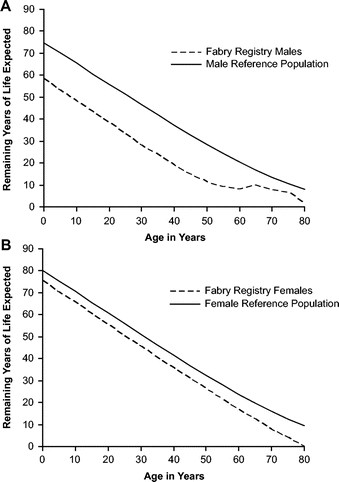

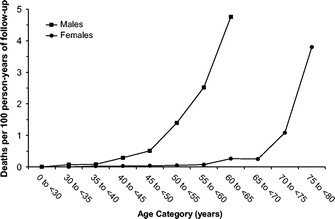

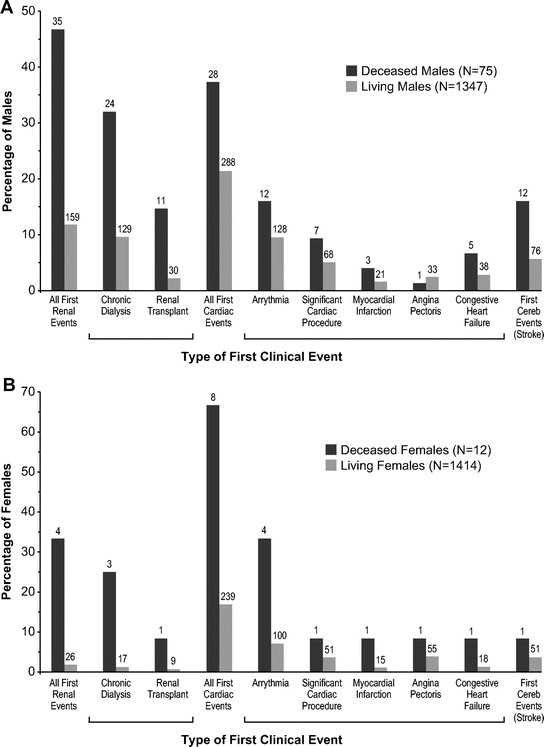

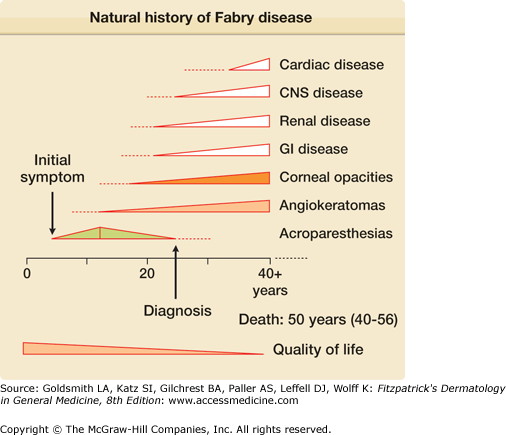

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in MedicineThanks for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To get best experience, we recommend you to use a more up-to-date browser (or turn off the compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continuous support, we are showing the site without styles and JavaScript.Warning Life expectancy and cause of death in men and women with Fabry disease: Fabry Record Conclusions volume 11, pages790-796(2009) Volume 113884 Accesses158 Citations26 AltmetricAbstractPurpose: Assess life expectancy and cause of death among patients with Fabry disease, a X-related lisomal storage disorder. Methods: The data of 2848 patients in the Fabry Registry were summed up using descriptive statistics. Life expectancy at birth is compared to that of the general population of the United States. Results: As of August 2008, 75 out of 1422 men and 12 out of 1426 women died in the Fabry Registry. The 87 deceased patients were diagnosed at a much older age than other patients in the Fabry Registry: the average age at diagnosis was 40 vs. 24 years in men and 55 vs. 33 years in women. The life expectancy of men with Fabry disease was 58.2 years, compared to 74.7 years in the general population of the United States. The life expectancy of women with Fabry disease was 75.4 years, compared to 8.0 years in the general population of the United States. The most common cause of death between both sexes is cardiovascular disease. Most (57%) patients who died of cardiovascular disease had previously received renal replacement therapy. Conclusions: Most of the deceased patients in the Fabry Registry exhibited severe heart and kidney dysfunction. Late diagnosis may have contributed to the early death of these patients. MainFabry disease is a rare X-related metabolic disease caused by insufficient activity of the α-galactosidase α-lysomal enzyme. This leads to the accumulation of glucolipids with α-galactosidic terminal links, particularly globotriaosylceramide (GL-3), in various tissues and types of cells. The progressive accumulation of glucolipids eventually impairs organ function. The incidence of Fabry disease has been estimated at 1 out of 40,000 to 1 out of 117,000 live births. This may be an underestimation, as patients with milder forms of the disease are not always diagnosed. There is no known predilection of Fabry disease for any specific race or ethnicity. The first symptoms of Fabry disease, including neuropathic pain in the extremities, hypohydrosis and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea and food intolerance, usually begin during childhood.– Later in life, many patients develop manifestations of life-threatening diseases, including chronic kidney diseases, cardiovascular diseases and strokes. Signs and symptoms of Fabry disease are generally more severe among hemizygous males; however, heterocigous heterocigous heterocigous heterocigous heterocigous heterocigous heterocigous often exhibit severe clinical manifestations that affect the quality of life and longevity, recompensing plasma therapy of Enzyme (ERT) with α- ,Lifespan is considerably shortened in men with Fabry disease. Before kidney dialysis and kidney transplants were widely available, the average death age among men with Fabry disease was reported as 41–42 years., The increase in availability of renal replacement therapy in recent decades has increased the useful life of Fabry patients. However, the life expectancy of patients with Fabry disease has not been formally analyzed. Since 2001, five relatively small cohort studies of patients with Fabry disease have reported survival data, and one study has reported cause of death data. In these studies, it was reported that men survived at a medium or medium age of 50 to 57 years, and women at a medium or medium age of 64 to 72 years., The Fabry Registry, which tracks the natural history and results of patients with Fabry disease, had enrolled 2848 patients, including 1422 men and 1426 women, as at 2 August 2008. Detailed analysis of life expectancy, clinical events and cause of death among men and women in this much larger cohort will provide valuable up-to-date information on the longevity and mortality of patients with Fabry disease. MATERIALS AND METHODS The Fabry Registry is an ongoing observation database that collects clinical and research data on patients with Fabry disease. It began to register patients and collect data in April 2001. All patients with Fabry disease are eligible to register, regardless of their age, sex, symptoms or if they are receiving ERT. The participation of patients and doctors is voluntary. All patients provided informed consent through local institutional review boards and ethics committees and may refuse to participate or withdraw consent at any time. The data collected by the Fabry Registry are entered into a database using a set of standardized reporting forms. The data were analyzed using version 8 of SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and were summed up using descriptive statistics. These analyses included all patients in the Fabry Registry with evaluation data, regardless of the status of enzyme treatment. The cause of death was reported by doctors who treated. Patients who were reported as deceased but for those who were not available the date of death were excluded from the analysis. The number of person-years of follow-up was calculated from the date of birth to the date of death or, for living patients, from the date of birth to the date of the last assessment of each patient. Life expectancy at birth was computed according to the standard methods of the living table and compared to the general population of the United States. The ethnic groups of the patients were self-reported and are included as a standard part of the demographic characterization of the cohort. Significant clinical events such as cardiovascular, stroke, or kidney were classified. Cardiovascular events were defined as myocardial infarction, significant heart procedures (e.g., pacemaker placement, coronary bypass, stent placement, valve replacement), arrhythmia, angina pectoris or congestive heart failure. Brain events are defined as strokes. Kidney events are defined as chronic dialysis (≥40 days) or kidney transplant. RESULTSAs of 2 August 2008, 75 out of 1422 men and 12 out of 1426 women in the Fabry Registry had died. Demographic data are summarized in . No significant differences were observed in ethnicity or in the geographic region between deceased patients and living patients. As shown in , the average age to death was 54.3 years in men (range, 31.2-84.8) and 62.0 years in women (range, 39.9–76.1). Both the living males and the deceased reported on the onset of Fabry symptoms at a median age of 10 years. The average age at the beginning of the symptom was lower in living women (15.2 years) than in deceased women (22.1 years), but this difference may not be significant, since there were only 12 women killed in the Fabry Registry (). Patients with Fabry disease were diagnosed at ages much older than living patients. Disadvantaged men were diagnosed at an average age of 39.8 years (range, 7.8–81.0), while living men were diagnosed at an average age of 24.4 years (range, 0–79.8). In addition, women died at a median age of 55.4 years (range, 23.8–72.5), compared to 32.7 years for women living (range, 0–80.6). In chronological terms, living patients were diagnosed more recently than deceased patients. In 1992 and 1999, respectively, disadvantaged men and women were diagnosed, compared to 2001 and 2003 for men and women in the Fabry Registry. Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of the Dead and Living Patients of the Fabry Registry As shown in, most men died between the ages of 40 and 60, while most women died at ages over 60. No Fabry Registry patient died before the age of 30. Sixty-one of the 75 deceased men (81.3 per cent) and five of the 12 deceased women (41.7 per cent) received ERT, which was made available for trade in Europe 2001 and the United States in 2003. The median duration of the time these patients were in ERT was 12 months in men and 4 months in women. The risk of mortality among all patients in the Fabry Registry is shown in . In men, the mortality rate increased from 40 years and increased faster to every 5-year increase over 50 years. As expected, it was documented that male patients had a higher mortality rate than women in all age categories. Women ' s mortality rate remained relatively stable to 60 years and rose rapidly after 65 years. Fig. 1Age at death for Fabry Registry patients. Percentages of patients who died during various age categories are shown. Data for men are in grey bars and data for women are in black bars, with the number of patients in each age category shown above each bar. Fig. 2Incidence of mortality in patients of the Male and Female Fabry Registry. The data are expressed as the number of deaths per 100 person years of follow-up time in various age categories. For patients who died from the Fabry Registry, the follow-up person years were defined as the number of years from birth to the date of death. For patients in the Fabry Registry, the follow-up person years were defined as the date of the last evaluation. The incidence of mortality was calculated by dividing the number of deaths in each age category by the total number of person-years of follow-up of each age category. Data for men are shown as squares and data for women are shown as circles. The life expectancy of patients in the Fabry Registry was calculated at 5-year increases, beginning from the date of birth. The Fabry Registry includes patients from 39 countries, with the majority of patients registered in the United States (35%) and in Europe (46%). The general population of the United States is used as a reference population, where life expectancy is 74.7 years in men and 8.0 years in women. There is no data available on the life expectancy of the European population in general, but the average life expectancy between 14 European countries ranges from 74.2 to 78.0 years in men and between 80.1 and 83.1 years in women. As shown in, Fabry's men had a substantially reduced life expectancy compared to the general population. At birth, the life expectancy of men was 58.2 years, compared to 74.7 years in the general population. Between the birth and the age of 60, the average life expectancy was 17 years less in Fabry's men compared to the men of the general population. Over 60 years, the life expectancy of men Fabry was closer to the general population; however, these data are based on relatively few male survivors. Only 93 of 1422 men in the Fabry Registry (6.5%) were ≥60 years old. The gap in life expectancy between women in the Fabry Registry and the general population is considerably lower. The life expectancy of Fabry women at birth was 75.4 years, compared to 8.0 years in the general population. In all age categories, average life expectancy was 6.4 years lower in Fabry women compared to the general population. The gap was slightly widened among patients over 70 years of age, reflecting again the small number of survivors of Fabry: 66 out of 1426 women in the Fabry Registry (4.6%) were over 70 years old. Fig. 3 Life expectancy of patients from the Fabry Registry. Panel A, Life expectancy of the men of the Fabry Registry (launch line) and men in the American general population (solid line), in years. Panel B, Life expectancy of women of the Fabry Registry (launch line) and women in the general population of the United States (solid line), in years. The reported cause of death was known to 56 of 75 men (74.7 per cent) and 10 of 12 women (83.3 per cent), as shown in . Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death between both sexes; 30 of the 56 men with a known cause of death (53.6%) and 5 of 10 women with a known cause of death (50.0%) had their deaths classified as due to cardiovascular disease. The average age of death due to cardiovascular disease was 55.5 years in men and 66.0 years in women. Among men with a known cause of death, the second and third most common cause of death were cerebrovascular disease (7 of 56, 12.5 per cent) and kidney disease (6 of 56, 10.7 per cent). Among the five males who died of infection (8.9% of males with known cause of death), one experienced sepsis after hemodialysis, one experienced septicemia after a kidney transplant, one experienced septicemia due to an urinary tract infection, and two had pneumonia, one of whose infections was reported to be secondary to congestive heart failure. A man committed suicide at the age of 31. The second most common cause of death among women with a known cause of death was cancer (3 of 10, 30.0%). Table 2 Cause of Death among Patients from the Fabry Registry Most of the 87 deceased patients of the Fabry Registry had experienced a serious cardiovascular, stroke or kidney event at some point, as defined in Methods. Sixty-eight out of 75 men (90.7%) and 10 out of 12 women (83.3%) experienced 1 or more clinical events prior to their death, as shown in . A much lower proportion of live patients have experienced clinical events: 478 out of 1347 living men (35.5%) and 283 out of 1414 living women (20.0%). As shown in , the first most common clinical events experienced by deceased men were renal events; 24 of 75 (32.0%) received chronic dialysis and 11 of 75 (14.7%) received a kidney transplant. Twenty-seven of 75 deceased men (37.3%) experienced some kind of cardiovascular event, the most common is arrhythmia (12 of 75, 16.0%). Twelve of 75 deceased men (16.0%) were beaten. Deprived females were more likely to have experienced cardiovascular events (8 out of 12, 66.7%) as their first clinical event than kidney events (4 out of 12, 33.3%). Arrhythmia was the most common type of first cardiovascular event among deceased women, although this data is based on relatively few patients; 4 out of 12 deceased women (33.3%) had arrhythmias. Table 3 Age in the first clinical event in deceased and living patients of the Fabry Fig Registry. 4Type of significant clinical events first experienced by patients of Fabry Registry. Panel A, The data is expressed as the percentage of all deceased or living men in the Fabry Registry who experienced the events indicated as their first clinical event. Panel B, The data is expressed as the percentage of all the deceased or living women in the Fabry Registry who experienced the events indicated as their first clinical event. Data for deceased patients are shown in black bars, and data for live patients are shown in grey bars, with the number of patients in each age category shown above each bar. Percentages of all patients with kidney events and all patients with heart events are shown along with percentages of patients with specific types of kidney and heart events (indicated in brackets). Note that six deceased men and two deceased women are included in several categories, because they experienced more than one type of first event on the same date. Cereb, cerebrovascular. Thus, although the most common cause of death among men was cardiovascular disease, renal events were more common as the first clinical event than cardiovascular events. Among the 30 men whose cause of death was classified as cardiovascular, 19 (63.3%) had also experienced a kidney event at some point. Two of the five females (40.0%) who died of cardiovascular disease had also experienced a kidney event during their lifetime. DISCUSSION The Fabry Registry has collected clinical data from a large international cohort of patients with Fabry disease, which allows the calculation of life expectancy. At birth, the life expectancy of Fabry's men was 58.2 years, compared to 74.8 years in the general population of the United States. Fabry's life expectancy at birth was 75.4 years, compared to 80.1 years in the general population of the United States. Patients with decline were much more likely to have experienced clinical events than living patients. This may be partly because the living patients were substantially younger at the time of their last follow-up visit than the deceased patients at the time of their death. Disadvantaged men had died at an average age of 54.3 years, while the median age at the last follow-up was 37.6 years among living men. Similarly, the average age of women of death was 62.0 years, compared to a median age of 41.9 years at the last follow-up visit for women living. Thus, living patients had less time to have experienced clinical events than older deceased patients. Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death in men and women with Fabry disease. However, renal replacement therapy (whether chronic dialysis or kidney transplant) was the most common type of clinical event that was experienced by deceased men, and most men who died of cardiovascular disease had previously received renal replacement therapy (19 of 30, 63%). Among the deceased women, renal replacement therapy and arrhythmia were the most common types of first clinical event. Thus, without kidney replacement therapy, many patients would have presumably died of kidney failure, instead of cardiovascular disease, at much younger ages., Kidney disease in general may be both a cause and a consequence of heart disease. In addition, it has been well determined that patients receiving kidney or hemodialysis transplants are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease. Consequently, cardiovascular and renal manifestations of the disease of less Fabry may be partially related. The impact and physiopathology of Fabry's disease is well known and has been the focus of many studies. – However, little is known about the progressive effect of Fabry disease on the cardiovascular system. Fabry disease has been established to lead to the accumulation of GL-3 in the vascular endothelium of the heart, as well as within cardiomyocytes., It is not known whether the deaths due to cardiovascular disease in this cohort were caused mainly by cardiovascular complications of Fabry disease or due to complications of the underlying kidney disease. Based on the involvement of vascular endothelio and myocardio, Fabry's disease can lead to cardiovascular death through multiple pathways. Five males were reported to have died of infection. There is no evidence that patients with Fabry disease are particularly susceptible to infection. Some of these infections are likely to arise as complications of the various medical procedures that Fabry's advanced disease patients require. A patient died of sepsis after hemodialysis and a second died of sepsis after a kidney transplant. In addition, cardiovascular disease is a known risk factor for pneumonia, which was reported as the cause of death in 2 men. Patients who died were diagnosed with Fabry disease at a relatively late age: average 40 years in men and 55 years in women. Consequently, the disease had progressed substantially before these patients were diagnosed, which probably contributed to their early death. Fortunately, today patients are often diagnosed with Fabry disease at a much older age; in 2007, the average age of diagnosis among the total population of patients in the Fabry Registry was 24 years in men and 31 years in women. Since cardiovascular disease was the most common cause of death, heart function should be closely monitored in patients with Fabry disease. All patients should be routinely monitored by standard electrocardiogram and 24 hours and echocardiogram, regardless of gender or if they have signs of heart disease. In addition, cardiologists should consider Fabry disease in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). A study of 153 males with HCM identified 6 patients (4%) who had undiagnosed Fabry disease. A second screening study of 508 patients with HCM, including 328 men and 180 women, reported that 1% of patients had undiagnosed Fabry disease. It is important to note that 61 of the 75 deceased men (81.3 per cent) and 5 of the 12 deceased women (41.7 per cent) in the Fabry Registry were known for having received ERT at some point. These patients were not treated for most of their lives, as the median duration of the ERT was 12 months in men (range, 0.1-7.3 years) and 4 months in women (range, 0.1-2.8 years). As noted above, the deceased patients were diagnosed at a relatively late age and were therefore likely to have been in the advanced stages of Fabry disease at the time of diagnosis, as well as at the time when they began receiving ERT. A recent report by Mehta et al. assessed the cause of death in patients enrolled in the Fabry Results Survey (FOS). Similar to the findings of the Fabry Registry, Mehta et al. reported that the most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (36%), followed by infection (15%), among the 42 patients whose deaths were reported between 2001 and 2007. The average ages in death are generally similar in the two studies: 51.8 years in FOS men against 53.7 years in Fabry Registry men and 64.4 years in FOS women versus 60.9 years in Fabry Registry women. Neither life expectancy nor age at diagnosis of deceased patients were reported by Mehta et al. The findings of both studies suggest that recent improvements in the treatment of kidney disease have led to a decrease in the deaths of Fabry patients due to kidney failure; more patients are currently dying of cardiovascular disease. The findings of these analyses are limited by the observational nature of the data reported to the records. For example, although a standardized definition of clinical events is provided in the Fabry Registry report form, an independent committee did not resolve all events. In addition, patients may be lost for follow-up and/or occurrence or time of clinical events or death cannot be captured. The previous diagnosis, guidelines for the treatment of children and the wider availability of ERT will allow patients to be treated earlier, either before reaching advanced stages of cardiovascular or kidney disease. Previous studies have shown that the ERT more effectively slows down the progression of renal decline, and myocardiopathy, when patients are treated early during the course of the disease. Consequently, the previous diagnosis and the initiation of treatment are expected to extend survival. The findings of these analyses highlight the burden of Fabry disease, which frequently leads to multiple serious clinical events and is associated with reduced life. Physicians who care for patients with Fabry disease should continue to carefully evaluate and identify disease progression and the involvement of final organisms, to institute treatments aimed at improving patient outcomes. ReferencesDesnick RJ, Ioannou YA, Eng CM . α-Galactosidase a deficiency: Fabry disease. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, ValleD, editors, Metabolic and molecular bases of hereditary disease. Eighth edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001: 3733–3774. Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, et al. Prevalence of lysomal storage disorders. JAMA 1999; 281: 249–254.281 Ries M, Ramaswami U, Parini R, et al. Early clinical phenotype of Fabry disease: a study on 35 European children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2003; 162: 767–772.162 Ries M, Gupta S, Moore DF, et al. Fabry pediatric disease. Pediatrics 2005; 115: e344–e355.115 Hopkin RJ, Bissler J, Banikazemi M, et al. Characterization of Fabry disease in 352 pediatric patients in the Fabry Registry. Pediatr Res 2008; 64: 550–555.64 MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of the disease in a cohort of 98 hemizygous males. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 750-760.38 MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH. Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of the disease in a cohort of 60 women mandatory carriers. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 769-775.38 Branton MH, Schiffmann R, Sabnis SG, et al. Natural history of Fabry kidney disease: influence of alpha-galactosidase Activity and genetic mutations in the clinical course. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81: 122-138.81 Mehta A, Ricci R, Widmer U, et al. Fabry disease defined: clinical manifestations of 366 patients in the Fabry Results Survey. Eur J Clin Invest 2004; 34: 236–242.34 Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, et al. Females with Fabry disease tend to have a significant involvement in the organs: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab 2008; 93: 112–128.93 Sims K, Politei J, Banikazemi M, Lee P. Fabry's disease often occurs before diagnosis and in the absence of other clinical events: natural history data from the Fabry Registry. Stroke 2009; 40: 788–794.40 Wang RY, Lelis A, Mirocha J, Wilcox WR. Heterocigous Discarded women are not just "carriers", but they have a significant burden of disease and a poor quality of life. Genet Med 2007; 9: 34–45.9 Vedder AC, Linthorst GE, van Breemen MJ, et al. Dutch Fabry Cohort: diversity of clinical manifestations and Gb3 levels. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007; 30: 68-78.30 Eng CM, Banikazemi M, Gordon RE, et al. A phase 1/2 clinical trial of enzyme substitution in Fabry disease: pharmacokinetics, substrate removal and safety studies. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 711–722.68 Eng CM, Guffon N, Wilcox WR, et al. International Collaborative Fabry Disease Study Group. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase replacement therapy in Fabry disease. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 9-16.345 Schiffmann R, Kopp JB, Austin HA III et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285: 2743–2749.285 Wilcox WR, Banikazemi M, Guffon N, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 75: 65–74.75 Germain DP, Waldek S, Banikazemi M, et al. Long-term sustained renal stabilization after 54 months of waltzidy beta therapy in patients with Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 1547-1557.18 West M, Nicholls K, Mehta A, et al. Agalsidase alpha and renal dysfunction in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 1132–1139.20 Hughes DA, Elliott PM, Shah J, et al. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy in Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy disease: a randomized, double-blind, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of alpha. Heart 2008; 94: 153–158.94 Weidemann F, Niemann M, Breunig F, et al. Long-term effects of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry cardiomyopathy: evidence for a better outcome with early treatment. Circulation 2009; 119: 524-529.119 Wise D, Wallace HJ, Jellinek EH. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Q J Med 1962; 31: 177–206.31 Colombi A, Kostyal A, Bracher R, et al. Angiokeratoma disease corporis diffusum-Fabry. Helv Med Act 1967; 34: 67–83.34 Mehta A, Clark JTR, Giugliani R, et al. FOS researchers. Natural course of Fabry disease: change of pattern of causes of death in the FOS - the results survey of the Fabry. J Med Genet 2009; 46: 548–552.46 Selvin S. Statistical analysis of epidemiological data. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991: 241–244.Hoyert DL, Heron MP, Murphy SL, Kung HC. Deaths: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2006; 54: 1–120.54 Jagger C. EHEMU Team; Healthy Life Expectancy in the EU15. Available in: . Accessed on April 22, 2009. Go ahead, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and death risks, cardiovascular events and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1296–1305.351 Elsayed EF, Tighiouart H, Griffith . et al. Cardiovascular disease and posterior kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1130–1136.167 Dimény EM. Cardiovascular disease after kidney transplant. Kidney Suppl 2002; 80: 78–84.80 Wanner C, Zimmermann J, Schwedler S, Metzger T. Inflammation and cardiovascular risk in dialysis patients. Suppl de Int de Riñón 2002; 80: 99-102.80 Chimenti C, Hamdani N, Boontje NM, et al. Degradation and dysfunction of human myocardiocytes in Fabry's disease. Am J Pathol 2008; 172: 1482–1490.172 Eng CM, Germain DP, Banikazemi M, et al. Fabry disease: guidelines for the evaluation and management of multiorgan system involvement. Genet Med 2006; 8: 539-548.8 Sachdev B, Takenaka T, Teraguchi H, et al. Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry disease in male patients with late-appearing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002; 105: 1407–1411.105 Monserrat L, Gimeno-Blanes JR, Marín F, et al. Fabry disease prevalence in a cohort of 508 patients not related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 2399–2403.50 Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Waldek S, et al. Fabry Disease Clinical Trial Study Group. Agalsidase-beta therapy for advanced Fabry disease. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 77–86.146 Recognition The Fabry Registry is sponsored by Genzyme Corporation. The authors thank the many patients who have agreed to participate in the Fabry Registry, as well as the doctors and research coordinators who have entered clinical data in these patients. The authors also recognize our colleagues from Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA), Dana Beitner-Johnson, PhD and Fanny O'Brien, PhD, for assistance with writing manuscripts and statistical analysis. Author's information Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom Stephen WaldekDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina Manesh R PatelDepartments of Neurology and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New YorkMaryam BanikazemiDepartments of Pediatrics, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in You can also search this author in Correspondence to the correspondent . Additional Information Dissemination: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Rights and Permits About this article Cite this article Waldek, S., Patel, M., Banikazemi, M. et al. Life expectancy and cause of death in men and women with Fabry disease: Conclusions of the Fabry Registry. Genet Med 11, 790–796 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bb05bb11, Received: April 29, 2009 Accepted: July 08, 2009 Published: September 10, 2009 Publication date: November 2009DOI: Keywords Borders in Cardiovascular Medicine (2021) Expert Opinion on Drug Safety (2021) Genetics in Chiquitos (2021) Reports of molecular genetics and metabolism (2021) Cells (2021) Explore ContentGeneral information Publish with usSearch Quick links Genetics in Chiquitos ISSN 1530-0366 (online) nature.com sitemap Discover contentPublication policiesAuthor & Research services Libraries and institutions Advertising and partnerships Professional development Regional websites Legal © 2021 Springer Nature Limited

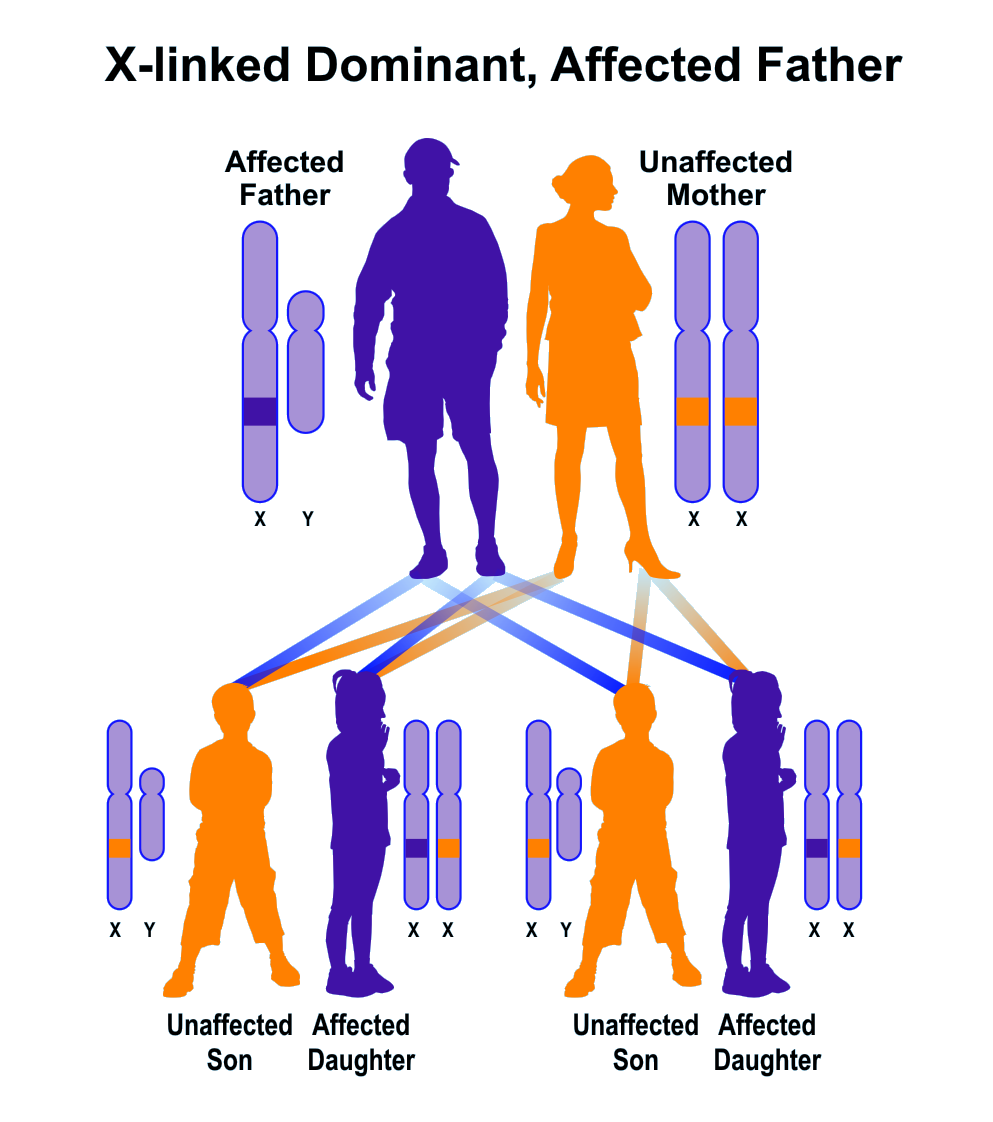

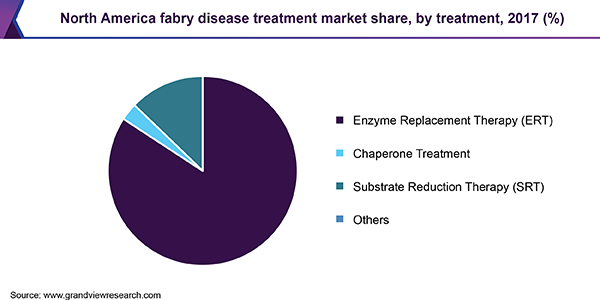

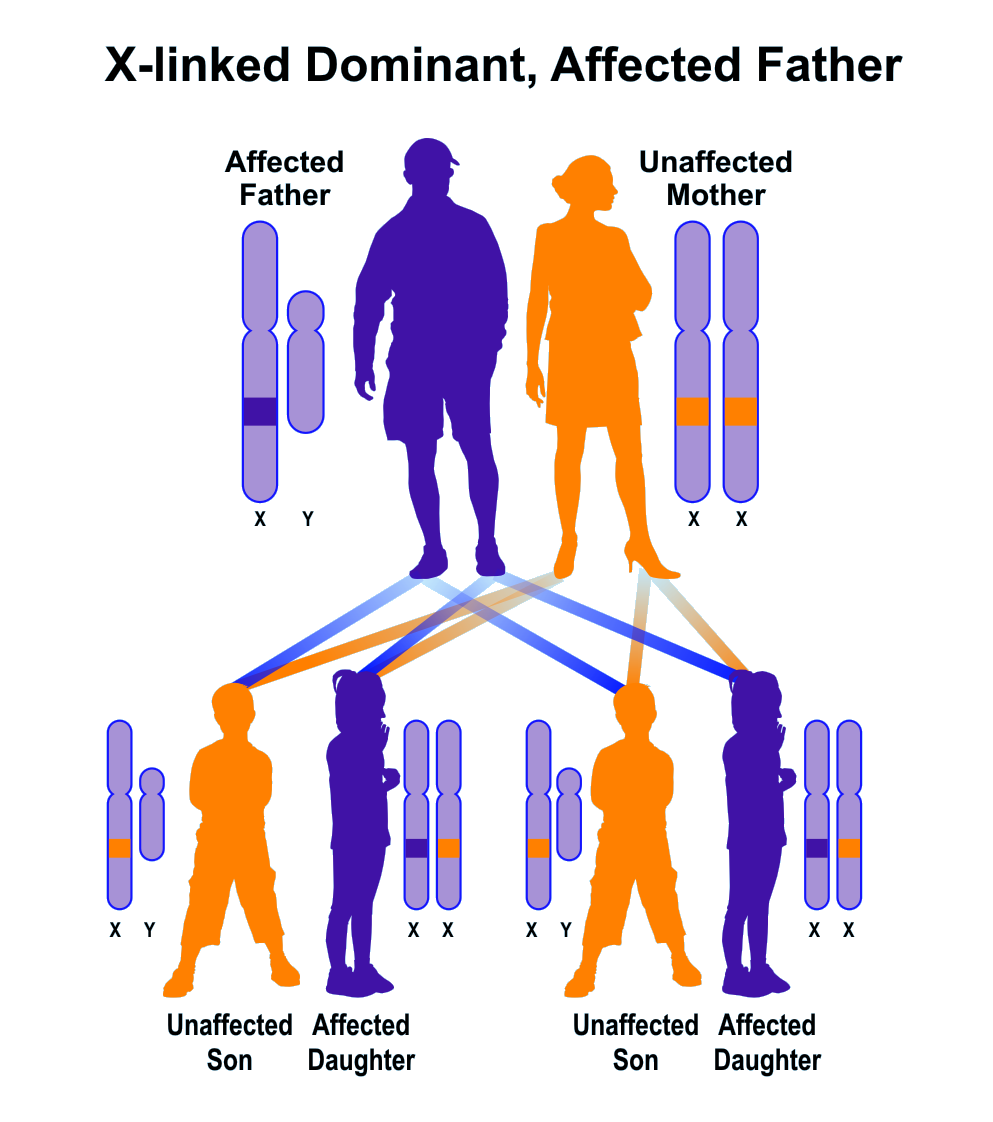

Understand Fabry's Disease What is Fabry's Disease? Fabry disease (FD) is a rare and inherited disease. It's progressive and can be life-threatening. People with FD have a damaged gene that leads to a shortage of an essential enzyme. Scarcity results in the accumulation of specific proteins in body cells, causing damage to:The disease affects both men and women in all ethnic groups, but men are often more affected. There are two types of FD. Type 1 FD, also known as classic FD, begins in childhood and is less common than type 2, which has a later start. It is estimated that FD.FD is appointed to Johannes Fabry, a doctor in Germany who . Also known as Anderson-Fabry disease, for William Anderson, a British doctor who also observed it in that same year. Other names for FD are: FD has many different symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Symptoms can vary between men and women, and between type 1 and type 2 FD. Type 1 symptoms Type 1 FD symptoms include: As type 1 FD progresses, symptoms become more severe. When people with type 1 reach their , they can develop kidney disease, heart disease, and stroke. Symptoms of type 2 FDTThose with type 2 FD also develop problems in these areas, although usually later in life, in their . Serious symptoms of FD vary from person to person and may include: Other signs of FD include: Who inherits the specific genetic mutation of FDA causes FD. You inherit the damaged gene from your parents. The damaged gene is found in chromosome X, one of the two chromosomes that determine your sex. The males have an X chromosome and a Y chromosome, and the females have two X chromosomes. A man with the mutation of the FD gene in chromosome X will always pass it to his daughters, but not to his sons. Children receive chromosome Y, which does not have the damaged gene. A woman with the FD mutation in an X chromosome has a 50 percent chance to pass it to her sons and daughters. If your child receives the X chromosome with the FD mutation, he will inherit FD. Because a daughter has two X chromosomes, she may have less severe FD symptoms. This is because not all cells in your body will activate the X chromosome that carries the defect. If the damaged chromosome X is activated or does not occur early in its development and remains this way for the rest of its life. How genetic mutations lead to FDFD are caused by as many as in the GLA gene. Individual mutations tend to run in families. The GLA gene controls the production of a particular enzyme called alfa-galactosidase A. This enzyme is responsible for breaking down a molecule in cells known as globotriaosylceramide (GL-3). When the GLA gene is damaged, the enzyme that breaks GL-3 down cannot work properly. As a result, GL-3 accumulates in the cells of the body. Over time, this accumulation of fat damages the cell walls of the blood vessels in:The degree of damage caused by the FD depends on the severity of the mutation in the GLA gene. That's why FD symptoms can vary from person to person. FD may be difficult to diagnose because symptoms are similar to those of other diseases. Symptoms are usually present long before diagnosis. Many people are not diagnosed until they have an FD crisis. Type 1 FD is most often diagnosed by doctors based on the symptoms of the child. In adults, FD is often diagnosed when tested or treated for heart or kidney problems. A diagnosis of FD for men can be confirmed by a blood test that measures the amount of the damaged enzyme. For women, this test is not enough, because the damaged enzyme may seem normal, although some organs are damaged. A genetic test for the defective GLA gene is necessary to confirm if a woman has FD. For families with known FD history, prenatal tests can be performed to determine whether a baby has FD. Early diagnosis is important. FD is a progressive disease, which means symptoms get worse over time. Early treatment can help. FD can cause a wide variety of symptoms. If you have FD, you will probably see specialists for some of these symptoms. In general, treatment will aim to control symptoms, relieve pain and prevent further damage. Once you are diagnosed with FD, it is important to see your doctor regularly to monitor your symptoms. People with FD are advised not to smoke. Here are some FD treatment options: Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT)ERT is now a recommended first-line treatment for all people with FD. Agalsidase beta (Fabrazyme) has been used since 2003, when it was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. It is given, or through a IV. Pain Management Pain management may involve avoiding activities that may cause symptoms, such as intense exercises or temperature changes. Your doctor may also prescribe medications such as diphenylhydantoin (Dilantine) or carbamazapin (Tegretol). These are taken daily to reduce pain and prevent the FD crisis. For your kidney A low protein and low sodium diet can help if it has a slightly reduced kidney function. If your kidney function gets worse, you may need kidney. In dialysis, a machine is used to filter the blood three times a week or more, depending on what type of dialysis you are on and how much you need. It may also be necessary. Necessary Treatments Heart problems will be treated as they are for people without FD. Your doctor may prescribe medications to manage the condition. Your doctor may also prescribe treatments to reduce the risk of stroke. For stomach problems, your doctor may prescribe medications or a special diet. A potential complication of FD is . ESRD can be fatal if it is not treated with dialysis or a kidney transplant. Almost all men with FD develop ESRD. But only about women with FD develop ESRD. For people who are treated to control ESRD, it is an important cause of death. FD cannot be cured, but it can be treated. FD consciousness is increasing. ERT is a relatively new treatment that helps stabilize symptoms and reduce the occurrence of FD crisis. Research is ongoing for other treatment possibilities. Genetic replacement therapy is in a clinical trial. Another approach in the research phase, called chaperon therapy, uses small molecules to stop the damaged enzyme. The life expectancy of people with FD is less than that of the American general population. For men, it is . For women, it is . A complication of FD frequently overlooked is . It may be useful to reach other people who understand. There are several organizations for people with FD who have resources that can help both people with FD and their families: Last medical review on June 6, 2017Read this below

Fabry Disease | Managing Patients

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

Fabry Disease | Managing Patients

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

Fabry disease

Fabry Disease Symptoms |Fabry Awareness

Fabry Disease | Managing Patients

Fabry disease

Fabry Disease Symptoms |Fabry Awareness![Screening, diagnosis, and management of patients with Fabry disease: conclusions from a]()

Screening, diagnosis, and management of patients with Fabry disease: conclusions from a "Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes" (KDIGO) Controversies Conference - Kidney International

Fabry disease awareness: an interview with Dr. Hartmann Wellhoefer, Head of Medical Affairs, Rare Disease, Shire

Fabry Disease | Managing Patients

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

▷ What is the life expectancy of someone with Fabry disease?

Fabry Disease – AVROBIO

Fabry Disease: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prognosis

Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients - ScienceDirect

Fabry Disease – AVROBIO

Typical signs and symptoms of Fabry disease according to age | Download Table

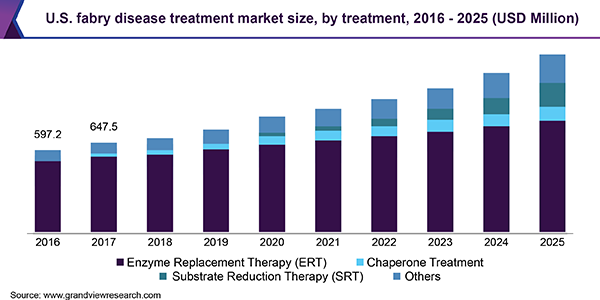

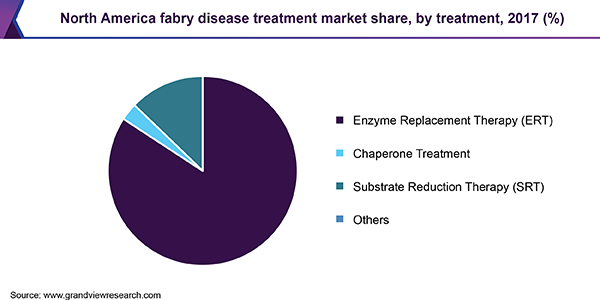

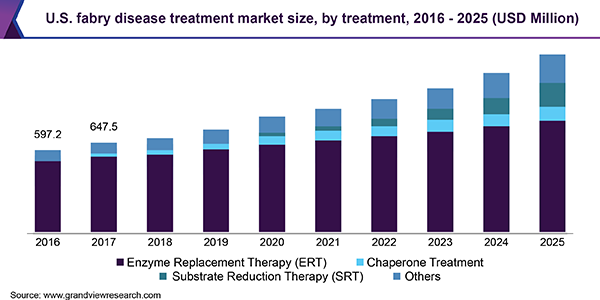

Fabry Disease Treatment Market Size | Industry Report, 2019-2025

AVROBIO, Inc. Announces Updated Clinical Data from Ongoing Phase 1 and Phase 2 Studies for AVR-

Fabry in the older patient: Clinical consequences and possibilities for treatment - ScienceDirect

Fabry disease: Symptoms, causes, and treatment

Fabry disease

Is Fabry Disease Going to Affect My Life Expectancy? - Fabry Disease News

Fabry Disease | Plastic Surgery Key

Clinical algorithm to classify patients with Fabry disease according to... | Download Scientific Diagram

Fabry Disease: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prognosis

Fabry disease - Wikipedia

Diagnostic algorithm for Anderson-Fabry disease shows the separate... | Download Scientific Diagram

Fabry Disease Treatment Market Size | Industry Report, 2019-2025

Proteomic assay for Fabry disease | mutation.me

Fabry Disease: Symptoms, Treatment and Life Expectancy

Fabry Disease – AVROBIO

Fabry Disease | Hereditary Ocular Diseases

Fabry's disease - The Lancet

The Changing Landscape of Fabry Disease | American Society of Nephrology

The Role of Cardiac Imaging in the Diagnosis and Management of Anderson-Fabry Disease - ScienceDirect

Fabry Disease disease: Malacards - Research Articles, Drugs, Genes, Clinical Trials

Evidence-Based Management of Patients with Fabry Disease | National Kidney Foundation

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry | Genetics in Medicine

Posting Komentar untuk "fabry disease life expectancy"