Can You Confuse Lucid Dreams with Reality?

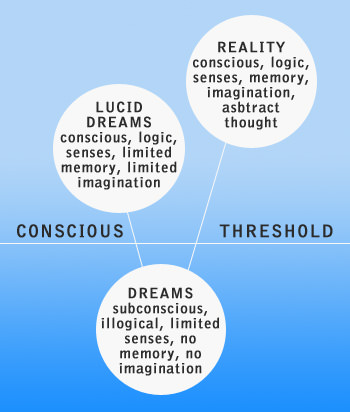

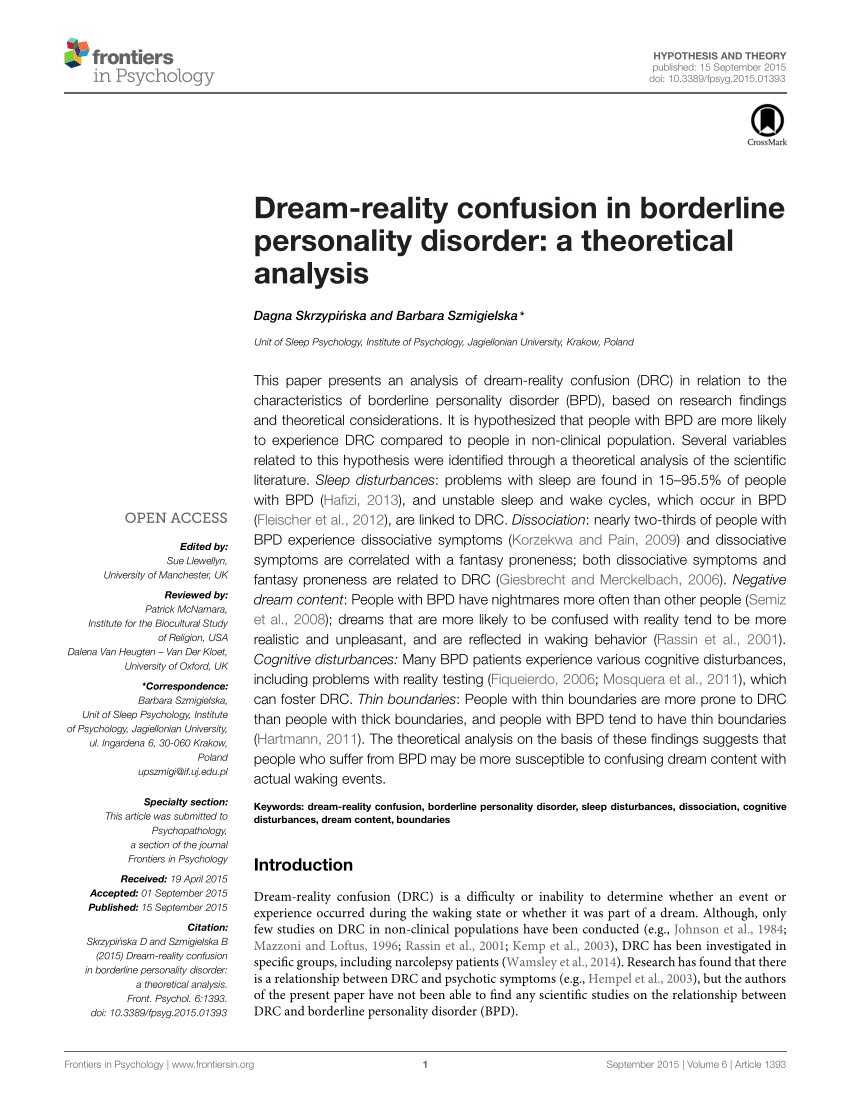

Can You Confuse Lucid Dreams with Reality?Impact factor 2.067 Silence CiteScore 3.2More on impact › Both psychopathology and creativity result from a labile candle sleep cycle? See everything 11 Articles Hypothesis and Theory Article confusion of sleep realities in border personality disorder: a theoretical analysis This document presents an analysis of the confusion between sleep and reality (DRC) in relation to the characteristics of border personality disorder (BPD), based on research findings and theoretical considerations. It is hypothesized that people with BPD are more likely to experience DRC compared to non-clinical people. Several variables related to this hypothesis were identified through a theoretical analysis of scientific literature. Sleep disorders: sleep problems are 15–95.5% of people with BPD (), and unstable sleep and candle cycles, which occur in BPD (), are linked to DRC. Dissociation: almost two thirds of people with BPD experience dissociative symptoms () and dissociative symptoms are correlated with a fantasy proneity; both dissociative symptoms and fantasy proneity are related to DRC (). Negative sleep content: People with BPD have nightmares more often than other people (); dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality tend to be more realistic and unpleasant, and are reflected in awakening behavior (). Cognitive disorders: Many patients with BPD experience various cognitive disorders, including problems with reality tests (; ), which can encourage DRC. Thick Limits: People with thin limits are more prone to DRC than people with thick limits, and people with BPD tend to have thin limits (). The theoretical analysis on the basis of these findings suggests that people suffering from BPD can be more susceptible to confusing the content of dreams with real awakening events. IntroductionConfusion in the reality of sleep (DRC) is a difficulty or inability to determine whether an event or experience occurred during the awakening state or whether it was part of a dream. Although only a few studies have been conducted on DRC in non-clinical populations (e.g. ; ; ), DRC has been investigated in specific groups, including narcolepsy patients (). Research has found that there is a relationship between DRC and psychotic symptoms (e.g., ), but the authors of this document have been unable to find any scientific study on the relationship between DRC and border personality disorder (BPD). The BPD is a generalized pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and affection, and a marked impulsivity that begins with early adulthood and is present in various contexts (DSM-V; , p. 663). To qualify for this diagnosis, the person should, among other symptoms, make a frenetic effort to avoid actual or imaginary abandonment, experience a chronic sense of vacuum or symptoms of temporary paranoid related to stress, or present severe dissociative symptoms. Moreover, persons with BPD often engage in self-destructive behaviours and are at significant risk of suicide. The border personality disorder affects between 1 and 5.9% of the general population (; ). Due to the complex psychopathology of the BPD, numerous studies have examined different areas of operation in individuals with this disorder. This theoretical analysis addresses the question of whether individuals with certain features of BPD may have difficulty distinguishing between dreams and reality. The objective of this document is to provide an overview of the current knowledge of the Democratic Republic of the Congo regarding the characteristics of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. We hypothesize that BPD subjects are very predisposed to experiencing DRC. This hypothesis is supported by the underlying assumption that there are groups of interrelated variables that are present both in the DRC and in the BPD. These variables, which we identify through an analysis of scientific literature, can be divided into the following categories: (i) sleep disturbances; (ii) dissociative symptoms; (iii) negative sleep content; (iv) cognitive disturbances; and (v) thin limits. This division was carried out on the basis of theoretical considerations; factors analysis has not yet been carried out. Each of these five variables is presented separately below. Variables present in BPD and DRCSleep disorders Sleep disturbances, for the purpose of this theoretical analysis, include a variety of sleep problems discussed below. Such sleep problems are very common among individuals with BPD (). Although there are few epidemiological data on sleep disorders among people diagnosed with BPD, cross-sectional studies show that sleep disorders prevail in 15–95.5% of this group (e.g., ; ; ; ).Compared to a non-clinical group, individuals with BPD take more time to sleep, sleep for shorter periods, have less sleep efficiency, and have frequent sleep disturbances (). The EEG recordings showed, for example, that participants in a BPD group, compared to a non-clinical population, had shorter sleep stages of NREM 2 and 4 and longer NREM sleep stage 1, and had high voltage delta waves during NREM sleep (; ). The REM dream was also different between groups, with BPD patients spending more time in the REM sleep, which had a longer latency, a first longer episode, and a greater REM density, as well as theta high voltage can and theta waves in the REM sleep, in participants with BPD (; ). Patients with BPD also have more nocturnal awakenings than people of a non-clinical population (; ). Frequent awakenings may cause difficulty in determining whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or was part of the sleep content (). Labile sleep cycles are another example of sleep disorders. They may occur in the course of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Police Directorate and are correlated with the Human Rights Commission (RC). Labile-wake sleep cycles can promote the intrusion of dreamed experiences in awakening consciousness that can lead to DRC and foster the feeling of depersonalization, which is a dissociative symptom. They also have an adverse effect on memory, thus favoring the creation of false memories (). Individuals who report sleep disorders mark high in dissociative scales, fantasy proneity (a tendency to deep and long-standing participation in fantasy and imagination; , p. 35) and are prone to false memories (). Together, previous relationships seem to support our hypothesis that BPD patients will likely experience DRC. It is suggested that a wide range of sleep disorders, such as labile-cloth sleep cycles, increase the tendency to experience nocturnal awakenings or nightmares (which are discussed in the "negative sleep content" section) in patients with BPD, which increases the likelihood that such people have problems distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or was part of sleep content. Dissociative symptoms Dissociation describes a state of disturbance and/or discontinuity in the integrated psychological functioning, such as consciousness, memory, identity or perception (DSM-V; ). Dissociative symptoms include derealization – the impression that the surrounding world or reality have changed, depersonalization – feeling as if one is an external observer of one's own self, and amnesia – an inability to remember, store and/or evoke memories. Dissociative states are experienced by approximately 2/3 of patients with BPD (). People diagnosed with BPD have a stronger tendency towards dissociative symptoms than the non-clinical population and individuals suffering from depression or schizophrenia (). The appearance of dissociative symptoms during the course of the BPD may be associated with child traumatic events. According to one of the theories of the etiology of the BPD, this personality disorder develops in individuals who report that traumatic events were a characteristic of their early lives, mainly physical abuse and emotional abandonment. A study of 139 patients with BPD found that those who had high scores in the Scale of Dissociative Experiences (DES), which measures the frequency of dissociative symptoms, such as autobiographic amnesia, derealization, depersonalization, absorption and alteration of identity (), experienced significantly more severe emotional and physical abandonment and emotional and physical abuse (but not sexual abuse) during childhood than those who had low scores). Results suggest that people exposed to severe traumatic events during childhood are more likely to develop dissociative symptoms. Traumatic experiences can contribute to the development of dissociative symptoms because trauma-related stress leads to a sudden discontinuity of the individual's experience, as it awakes fear of security and disrupts the connection between the inner and outer environment. Traumatic experiences also often interfere with the integration of mental functions, leading to their dysfunction (). In addition, dissociative symptoms involve automatic avoidance strategies that defend the consciousness of traumatic memories (). It should be noted that dissociative symptoms are one of the correlates of the DRC (). , p. 157) noted that derealization is a commitment between dreaming and awakening. It seems that frequent experiences of dissociative symptoms or their intensification can cause frequent intrusions of dreams in experiences during the state of vigil. Dissociative symptoms and the proneity of fantasy – features linked to DRC – are correlated, and it seems that this correlation can be mediated by experiences during sleep (). High-level students of fantasy-prone report more dissociative symptoms than their friends who mark low or medium in fantasy-proneness (; ). In addition, individuals who find it difficult to discriminate between dreams and higher score reality in scales that measure dissociative symptoms and fantasy proneity that individuals who do not confuse sleep content with experiences during the awakening state (). A study of 51 women in the general population found that the proneity of fantasy is linked to both dissociative symptoms and daily cognitive failures (). In addition, dissociative symptoms, fantasy proneity, cognitive failures and sleep disturbances are correlated (). Later in this document, we present data that indicate that the disturbances in cognitive functioning are among the variables that increase proneity towards the DRC. The relationship between dissociative symptoms and the proneity of fantasy has also been observed in clinical populations. It demonstrated such relationships in groups of subjects diagnosed with BPD, schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. In addition, it was found that dissociative symptoms related to impulsivity in people with the BPD. This association is interesting because impulsivity is one of the diagnostic characteristics of BPD (DSM-V, ).In short, the previous findings support our hypothesis that people with BPD diagnosis are more likely to experience DRC because of their tendency to experience dissociative symptoms and related phenomena, such as fantasy proneity, sleep disturbances and cognitive problems. Negative Dream Content Individuals suffering from BPD experience more negative life events than other individuals, even those with other personality disorders (). According to the classical continuity hypothesis (; ), dreaming reflects the dreamer's life experience, therefore the dream content of patients with BPD can be more negative than other people's dream content. The quantitative analysis of a group of 27 people diagnosed with BPD and a non-clinical group of 20 individuals showed that the BPD group had dreams with more negative impact than those of the non-clinical group. Generally, people suffering from BPD experience negative dreams, including nightmares, more often than people who have none of the symptoms characteristic of this personality disorder (). SNightmares are sleep disorders related to sleep disorders. They are defined as living dreams, loaded with negative emotions that awaken the dreamer of sleep (DSM-V; ). About 49% of patients with DB are affected by nightmares, while the prevalence of nightmares in the non-clinical population is estimated to be about 4–10% (; ). The increased frequency of nightmares among BPD patients compared to the non-clinical population is related to increased emotional instability and increased neuroticism in this clinical group (). The intensity of BPD symptoms is positively correlated with the frequency of nightmares (). To try to explain the prevalence of nightmares in people with BPD, we present two theories: a model of nightmare proposed by , and the model of emotional cascade developed by . proposed a theory to explain the occurrence of dysphoric dreaming, which is based on two main assumptions: the continuity between states and the multilevel explanation. The first, interstate continuity, supposes that some structures and processes involved in the production of nightmares are also dedicated during the expression of pathological signs and symptoms such as dissociative symptoms during the awakening state (p. 495). The second, the multilevel explanation, refers to the idea that the formation of nightmare can be explained in two different levels: the cognitive-emotional level and the neuronal level. At the cognitive-emotional level, there are imaging processes that represent emotional sleep images, while the neuronal level contains a network of brain regions responsible for imagistic and emotional processes. This model was created to explain the occurrence of nightmares in the course of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); however, it can also be used in an attempt to describe experiences related to both nightmares and interstate continuity in patients diagnosed with BPD. We will not discuss the concept of neuronal correlations of the DRC and the DB, as this is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we will focus on the notion of interstate continuity with reference to the BPD. In its model, consider a number of factors that underlie the continuity of the state, such as the burden – a factor of the state is the combined influence of stressful and emotionally negative events on the ability of an individual to effectively regulate emotions (p. 497), and affect the anguish – a trait factor is a long-standing trend and willingness to experience greater anguish and negative effect, and react with extreme behavioral expressions (p. 498). Other factors include high degrees of physiological and psychological reactivity, maladaptive coping, fantasy proneity, vividness of images and thin limits. Numerous studies suggest that almost all of these factors are usually present during the BPD course, but more recent studies indicate that there is no physiological reactivity intensified in BPD (e.g. ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). People diagnosed with this personality disorder are characterized by emotional disregulation, which is the inability to respond and manage emotions flexibly, which involves emotional sensitivity, high regulation and lay regulation. In addition, the BPD implies affective instability and a low level of recognition of emotions (). According to the biosocial theory, which explains the etiology of the BPD, this personality disorder develops in children (i) who have a biological propensity to experience negative effects, and (ii) who are in an invalid and toxic social environment. In the BPD, the biological sensitivity to emotional stimuli, the greatest negative effect, and a slow return to the emotional base are connected with difficulty to discriminate and label the emotional states themselves, starting appropriate strategies to manage these emotional states and being able to reduce intense negative affective states. Studies confirm that BPD patients show a negative distortion in identifying their own emotional states and emotional states of others (e.g., ). The inability to accurately recognize emotional states can intensify negative effects, emotional instability and emotional reactivity in everyday life. In addition, patients with BPD cannot tolerate discomfort and often use maladaptive regulation strategies to cope with the anguish and negative emotions they experience, such as rumins, impulsive behaviors or cognitive avoidance (). Emotional process disorders in patients with BPD seem to occur not only in the state of vigil, but also during sleep, as in the case of nightmares (). We hypothesize that astonishment and dreaming states may involve similar experiences; therefore, people with BPD may have difficulty discriminating if an event/experience occurred during the state of astonishment or was part of the dream content. Emotional disregulation, which is one of the factors associated with nightmares in theory, is also mentioned in its model of emotional cascade (ECM). The NDE tries to explain the etiology of the bad dreams experienced during the BPD. The effects of nightmares and other bad dreams, in addition to the fear they produce, can involve deficits in appropriate emotional regulation skills and diminish the ability to face the anguish during the next day, according to the NDE. Patients with BPD experience emotional cascades during the wave state, and this negative effect induces rumination – repetitive thoughts with mainly negative content. Ruminations increase the negative effect, which in turn intensify the rumins. These processes cause increased cognitive activity during sleep that favors the emergence of nightmares and maladaptive behaviors during the state of vigil that are intended to cope with negative emotions. It seems that frequent nightmares in people with BPD can influence the occurrence of negative life events (). Generally, a simplified model of emotional cascades assumes the successive occurrence of: negative emotional experiences during the awakening → increase of the rumins → increase of negative emotions → increase of the rumins → a very aversive emotional state → / possible dysfunctional coping skills connected with impact regulation (e.g., auto-chain, use of substances) / → high cognitive activity during the negative sleep cascades during the nightmare ) High cognitive excitation during sleep can cause awakening or semi-awakening, which can therefore lead to difficulty distinguishing between dreaming and awakening experiences (; ). In addition, the inability to effectively address stressful situations can increase the trend towards dissociative states (), which can eventually lead to a higher probability of DRC. In addition, a proven study that dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality are realistic, impregnated with negative impact, and give rise to behaviors in the state of awakening. However, because patients with BPD have more negative experiences in both the state of waste and the state of sleep and more cognitive disturbances, they may have more difficulty recognizing whether an event or experience occurred during the state of waste or was part of a dream. Overall, findings suggest that frequent unpleasant sleep content in the BPD can be a factor that increases proneness to the DRC. Cognitive Disturbing Patients with BPD may experience a number of different cognitive alterations. These include problems with metacognitive monitoring, which refers to the ability to observe one's own thinking processes, as well as to detect errors in its own reasoning, and inconsistencies in its own narratives. Metacognitive monitoring refers to "thinking in thought." Metacognitive knowledge, which is the ability to notice that some things/events may not be as they seem to be, is also distorted in the BPD (). Executive functions, such as working memory and inhibition of response, are usually also disrupted in the BPD (). On the other hand, the BPD is characterized by deficits in the processing of feedback, alteration of social inference and poor decision-making skills (; ). Generally, four types of cognitive disturbances are distinguished in the BPD: (i) transient, quasi-psychotic cognition, (ii) dissociation, (iii) social cognitive biases, and (iv) neurocognition). However, a detailed description of cognitive problems in the BPD is beyond the scope of this document. What is important is that problems with the evidence of reality can occur in patients with BPD (). The monitoring of reality, which is related to the testing of reality, seems to play a significant role in the process of distinguishing the content of dreams from awakening experiences. Monitoring of reality, a type of monitoring of sources, is defined as the ability to discriminate between memories of real events, and memories of dream events, imagination or delusions. The monitoring of reality consists of two decision-making processes: (i) evaluation of whether the characteristics of a memory stroke are more typical of memories of external events or memories generated internally; and (ii) evaluation based on current memory/knowledge, which is a more complex process and takes longer. The source of memory is distinguished on the basis of its characteristics: memories of actual events include more perceptual and contextual details, while memories of consciously imagined events include traces of cognitive operations that were involved in their creation. Dreams are classified as internally generated events, which are difficult to distinguish from external similar events because they are created without conscious cognitive operations (). In the case of dreams, conscious cognition, which is the most important point that would help to differentiate between memories generated internally and those generated externally is not present. These findings indicate that the DRC may be associated with difficulties with the monitoring of reality. The temporary suspension of the source monitoring process, together with the reduced capacity to respond to a sensory stimulus and reduced attention, is one of the common features of both dreaming and awakening fantasy. These processes can make it more difficult to distinguish between the content generated during sleep and the fantasy of awakening. Both the fantasy of awakening and the dreams play an integral role in the regulation of mood, the processing of adaptive information and the maintenance of self-cohesion by providing work templates for the future behavior directed by objectives and the development and maintenance of self-school (). BPD patients exhibit certain cognitive disorders that make them more prone to problems related to the tests of reality, and awakening fantasy can also disrupt the processes involved in correct monitoring of sources. In addition, it seems that mood regulation is disrupted in BPD due to a more negative sleep content and emotional cascades at night (). Cognitive and emotional processes during dreaming and awakening interact, and their interaction can contribute to the difficulty of distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the state of awakening or a dream. In addition, people who are more likely to make cognitive mistakes are less likely to rely on their cognitive skills (); therefore, they may be more sensitive to other people's suggestions. We hypothesize that people with BPD who have some cognitive deficits will rely less on their cognitive processes because they are not sure if their perception of reality is correct. Our assumption is that due to their cognitive disturbances, people with BPD, compared to non-clinical populations, will most often not be sure what the source of certain events or experiences (see v. reality), and may even do incorrect judgments about their source. The difficulty that BPD patients encounter in the test of reality () and their problems with metacognitive monitoring and metacognitive knowledge () appear to be the only examples of cognitive disturbances that could lead to a greater probability of experiencing DRC, compared to people of non-clinical populations. Thin Boundaries The concept of limits, which was defined by , refers to a wide spectrum of limits in the mind, including the interpersonal limits (self vs. others), the limits between the self and the outside world, and the limits between different states of consciousness (e.g., the awake state or dream state). Therefore, the limits refer to: (i) the connection between various aspects of the mind (i.e., the relationships between thoughts, emotions and memory), including the relationships between the personal past, the future and the present; and (ii) the connection between the self and the outside world (). People have been characterized by thin or thick limits (; ). Since the limits are generally stable through situations, there is a high probability that individuals with thin limits in certain areas have thin limits in other areas (). Patients with BPD tend to have thin limits (), and individuals with thin limits have greater sleep memory than those with thick limits. They also experience more emotions in their dreams, have more negative and emotionally intense dreams, dream more often of verbal interactions with others, and consider their most significant and creative dreams (). A memory of higher sleep and other vivid experiences of the night are associated with a greater tendency to absorption, which is a state of greater imaginative participation in which an individual's attention abilities focus on behavioral domain, often the exclusion of explicit information processing in other domains and fantasize (p. 203). showed that absorption is correlated with greater creativity, a tendency towards dissociation and greater involvement in activities based on imagination, with concomitant alterations in consciousness (). In this context, it may be interesting to ask questions about whether a greater ability to remember dreams increases the likelihood that sleep content is confused with real events. As patients with BPD have a higher tendency to absorb (), they would experience the DRC more often, perhaps in relation to other variables discussed in this document. The thick limits seem to improve the intrusion of dream content in the consciousness in the wave state, which can lead to difficulty distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or in a dream (). In addition, these intrusions may favor the emergence of dissociative symptoms, which, as mentioned above, are correlated with the DRC (; ). These data suggest that individuals with fine limits can be more prone to DRC. Therefore, patients diagnosed with BPD may also be more likely to be more likely to DRC. Taking into account the above considerations, it would be interesting to undertake studies on the relationship between creativity and DRC in BPD populations and non-clinical populations. Although a recent study found a moderate correlation between state dissociation and creativity, there was no significant correlation between creativity and unusual sleep experiences. Future studies should include the DRC as a construct to clarify its relationship with creativity. Conclusions The above paragraphs describe the variables that can lead to a greater tendency to experience DRC in DBPD patients. Taking into account everything, we propose a tentative model that patients with BPD are more likely than the non-clinical population to experience difficulties or an inability to determine whether an event or experience occurred during the state of vigil or was part of a dream. Patients with diagnosed DB may be more likely to experience dissociative symptoms due to traumatic events in their early childhood (), and dissociative symptoms are DRC correlates (). Thus, the greatest trend towards dissociative symptoms among people with BPD can make them uncertain if something they remember happened in their dreams or while they were awake. Dissociative symptoms are correlated with the proneity of fantasy, which is also correlated with DRC (; ; ). In addition, people with BPD often suffer from several sleep disorders (), and sleep disorders (e.g. nightmares) and unusual sleep experiences are related to dissociative symptoms and DRC (; ). In addition, patients with BPD experience negative emotions during awakening that are related to negative emotional experiences during sleep (). This process can also be connected to the high cognitive excitation during the dream that causes awakening or semi-awakening, which leads to the difficulty of distinguishing between dream experiences and awakening (; ). Furthermore, dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality are realistic, evoke negative emotions, and give rise to behaviors in the state of awakening (). The sleep content of patients with BPD is more negative than the sleep content of individuals in non-clinical populations, and people with BPD tend to experience a number of different cognitive alterations, such as problems with reality tests, metacognitive deficits, disruption of social inference, poor decision-making skills or cognitive distortions (; ; ; ; ; ; ). In addition, people with BPD are characterized by thin limits (), which can further improve confusion between dreams and awakening. This theoretical analysis, including variables such as sleep disorders, dissociative symptoms, negative sleep content, cognitive dysfunction and thin limits leads to the proposition that patients with BPD can be more prone to DRC, compared to non-clinical population. Future research on the general working model should involve the use of factor analysis and structural equation modeling to identify and confirm important variables and explore the complex relationships between these variables. We plan to conduct an empirical verification of these relationships. The aim of this comprehensive research program is not only to examine whether patients with BPD are more vulnerable than others to experiencing DRC, but to study in a comprehensive way the psychological and neuropsychological aspects of sleep and dreams, using subjective methods and objectives, in a continuum: BPD – some features of BPD – lack of BPD. The theoretical analysis presented above is exploratory in nature and aims to serve as a starting point for more advanced analysis, and to provide a theoretical basis for the planning of empirical studies. Conflict of interest The authors state that the investigation was conducted in the absence of commercial or financial relations that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest. References American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Association. Aragonés, E., Salvador-Carulla, L., López-Muntaner, J., Ferrer, M. and Piñol, J. L. (2011). Registered prevalence of border personality disorder in primary care databases. Gac. Sanit. 2, 171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.12.006 Silence Asaad, T., Okasha, T. and Okasha, A. (2002). Sleep EEG findings in border personality disorder ICD-10 in Egypt. J. Affect. Disord. 71, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00357-3 Silence Battaglia, M., Ferini-Strambi, L., Smirne, S., Bernardeschi, L., and Bellodi, L. (1993). Abulent polysomnography of never-depressed border subjects: a high-risk approach to the latency of the rapid eye movement. Biol. Psychiatry 33, 326–334. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90321-4 Silent Benson, K.L., King, R., Gordon, D., Silva, J. A. and Zarcone, V. P. (1990). Sleep patterns in border personality disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 18, 267–273. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90078-M TOP Bernstein, E. M., and Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability and validity of a scale of dissociation. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 174, 727-734. doi: 10.1097/000053-198612000-00004 Silence Briere, J. (2002). "Treat adult survivors of severe child abuse and neglect: development of an integrative model", in the APSAC Manual on Child Abuse, 2nd Edn, Edn, J. E. B. Myers, L. Berliner, J. Briere, C. T. Hendrix, T. Reid and C. Jenny (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications). Carpenter, R. W. and Trull, T. J. (2013). Components of disregulation of emotions in border personality disorder: a review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 15, 335. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0335-2 Silence viv Cavazzi, T., and Becerra, R. (2014). Psychophysiological research of the Border Personality Disorder: review and implications for the Biosocial Theory. Eur. J. Psychol. 10, 185–203. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v10i1.677 TENIDO Cole, P. M., Llera, S. J., and Pemberton, C. K. (2009). Emotional instability, low emotional awareness and the development of the border personality. Dev. Psychopathol. 21, 1293–1310. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990162 Silence Fertuck, E. A., and Stanley, B. (2006). Cognitive disorder in border personality disorder: phenomenological findings, social cognitive and neurocognitive. Curr. Psycho. Ther. Rep. 4, 105–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02629331 Silence Fiqueierdo, L. C. (2006). Sentence of reality, evidence of reality and reality processing in patients with borderline. Int. J. Psychoanal. 87, 769–787. doi: 10.1516/8Q72-R1Q6-N144-H0G6 TO ANTERIVIO FILISCAR, M., Schäfer, M., Coogan, A., Häßler, F., and Thome, J. (2012). Sleep disorders and circadian CLOCK genes in border personality disorder. J. Neural. Transm. 119, 1105–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0860-865 ANTERITO ANTERIEND Giesbrecht, T., and Merckelbach, H. (2006). Dream to reduce fantasy? – Fantasy proneness, dissociation and subjective sleep experiences. Pers. Individ. Dif. 41, 697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.015 Silence Hafizi, S. (2013). Sleep disorder and border personality: a review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 6, 425–459. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12048 Silence Hagenhoff, M., Franzen, N., Koppe, G., Baer, N., Scheibel, N., Sammer, G., et al. (2013). Executive functions in border personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 210, 224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.05.016 Silence Atlantic, C. S. and Nordby, V. J. (1972). The Individual and His Dreams. New York, NY: New American Library. Hartmann, E. (2011). Limits. Summerland: CIRCC - Never Press. Hartmann, E., Elkin, R. and Garg, M. (1991). Personality and Dream: the dreams of people with very thick or very thin limits. Dreaming 1, 311-324. doi: 10.1037/h0094342 Silence Hempel, A. G., Felthous, A. R., and Meloy, J. R. (2003). Psychological assault related to dreams: a critical review and proposal. Aggressive. Violent Behav. 8, 599-620. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(02)00105-2 strain Hunt, M. (2007). Disorder of the border personality throughout life. J. Women 19, 173-191. doi: 10.1300/J074v19n01_11 ← Silence Johnson, M. K., Kahan, T. L. and Raye, C. (1984). Dreams and monitoring of reality. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 113, 329-344. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.329 Silence Kemp, S., Burt, C. D., and Sheenm, M. (2003). Remembering dream and real experiences. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 17, 577–591. doi: 10.1002/acp.890 ANTERITO ANTERIORKZKKwa, M. I., and Pain, C. (2009). Border Personality Dissociation and Dissociation: an update for clinicians. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 11, 82–88. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0013-11 TEN Kuo, J. R., and Linehan, M. (2009). Disentangling thrill processes in Borderline Personality Disorder: physilogical and self-reported assessment of biological vulnerability, baseline intensity, and reactivity to emotionally evocative stimuli. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 531-544. doi: 10.1037/a0016392 Silence Silence Silence La Fuente, D., Manuel, J., Bobes, J., Vizuete, C., and Mendlewicz, J. (2001). Sleep-EEG in border patients with no major depression concomitant: a comparison with the main depressants and normal control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 105, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00330-4 Silence Levin, R., and Nielsen, T. A. (2007). Disrupted sleep, post-traumatic stress disorder and affect anguish: a model of review and neurocognitive. Psychol. Bull. 133, 482-528. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.482 Silence for the Levin, R. and Young, H. (2002). The relationship of awakening fantasy to dream. Imagine. Cogn. Pers. 21, 201–2019. doi: 10.2190/EYPR-RYH7-2K47-PLJ9 ← Levitan, H. L. (1967). Depersonalization and sleep. Psychoanal. Quart. 36, 157 to 171.Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of border personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford.Lynn, S. and Rhue, J. (1988). Fantasy proneity: hypnosis, a history of development and psychopathology. Am. Psychol. 43, 35–44. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.43.1.35 Silent Mak, A., and Lam, A. (2013). Neurocognitive profiles of people with personality disorder online border. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 26, 90-96. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835b57a9 Silence Silence Mazzoni, G. A. L., and Loftus, E. F. (1996). When dreams come true. Aware. Cogn. 5, 442–462. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1996.0027 Silence TENTED Merckelbach, H., Campo, A., Hardy, S., and Gersbrecht, T. (2005). Fantasy dissociation and proneity in psychiatric patients: a preliminary study. Compr. Psychiatry 46, 181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.08.001 Silence to live Merckelbach, H., Muris, P., and Rassin, E. (1999). Proneity of fantasy and cognitive failures as correlates of dissociative experiences. Pers. Individ. Dif. 26, 961–967. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00193-7 tención Morey, L. C. (2014). The characteristics of the border line are associated with self-esteem of inaccurate traits. Borderline Personal. Disordered. Emot. Dysregul. 1, 4. doi: 10.1186/2051-6673-1-4 Silence Mosquera, D., Gonzalez, A., and van der Hart, O. (2011). Border personality disorder, child trauma and structural personality dissociation. Rev. Pers. 11, 44–73. Silence Pagano, M. E., Skodol, A. E., Stout, R. L., Shea, M. T., Yen, S., Grilo, C. M., et al. (2004). Stressive life events as predictors of operation: findings of the collaborative study of the longitudinal personality. Acta Psychiatrist. Scand. 110, 421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00398.x Silence Philipsen, A., Feige, B., Al-Shajlawi, A., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., Richter, H., et al. (2005). Increased delta power and discrepancies in objective and subjective measurements of sleep in border personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 39, 489-498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.002 Silence Silence Plante, D. T., Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., and Fitzmaurice, G. M. (2009). Sedative-hypnotic use in patients with border personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J. Pers. Disord. 23, 563–571. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.6.563 Silence live Rassin, E., Merckelbah, H., and Spaan, V. (2001). When dreams become a real way for confusion: realistic dreams, dissociation and fantasy proneity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 189, 478–481. doi: 10.1097/000053-200107000-00010 Silence Silence Rauschenberger, S. L., and Lynn, S. J. (1995). Prophetic fantasy, DSM-III-R Axis I psychopathology and dissociation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 104, 373–380. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.2.373 Silence Silence Sansone, R. A., Edwards, H. C. and Forbis, J. S. (2010). Sleep quality in border personality disorder: a cross-sectional study. Prim. Look out for Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 12. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00919bro Silence Schredl, M. (2003). Continuity between awakening and dreaming: a mathematical model proposal. Sleep hipn. 5, 26-39.Schredl, M., Paul, F., Reinhard, I., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Schmahl, C., and Bohus, M. (2012). Sleep and dream in patients with border personality disorder: a polysomnographic study. Psychol. Res. 200, 430-436. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.036 Silence Silence Schredl, M., Schäfer, G., Hofmann, F. and Jacob, S. (1999). Dream and personality content: thick vs. thin limits. Dreaming 9, 257–263. doi: 10.1023/A:10213361035 Sil Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D. and Joiner, T. E. Jr. (2013). What dreams can come: emotional cascades and nightmares in borderline personality disorder. Dreaming 23, 126-144. doi: 10.1037/a0032208 TENIENDO Semiz, U. B., Basogolu, C., Ebrinc, S., and Cetin, M. (2008). Nightmare disorder, sleep anxiety and subjective sleep quality in patients with border personality disorder. Clin Psychiatry. Neurosci. 62, 48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01789.x Silence Sharma, V., and Singh, T. B. (2012). Cognitive treatment and emotional regulation in border personality disorder. Delhi Psychiatry J. 15, 279–286.Simor, P., Csóka, S., and Bódizs, R. (2010). Pesadillas and nightmares in patients with border personality disorder: ghosts as ability to cope? Eur. J. Psychiat. 24, 28–37. doi: 10.4321/S0213-61632010000100004 ← Steiger, H., Leonard, S., Kin, N. Y., Ladoucer, C., Ramdoyal, D., and Young, S. N. (2000). Child abuse and tritiada-paroxetine bonding of platelets in bulimia nervosa: implications of border personality disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61, 428-435. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v61n0607 Silence Torgersen. S., Kringlen, E., and Cramer, V. (2001). The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590 ← Trajanovic, N., Radivojevic, V., Kaushansky, Y. and Shapio, C. M. (2007). Positive state-of-the-sleep state-of-the-art concept of misperception of sleep. Sleep Med. 8, 111–188. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.08.013 Silence Trivedi, J. K. (2006). Cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders: current state. Indian J. Psychiatry 48, 10–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31613 Silence van der Kloet, D., Merckelbach, H., Giesbrecht, T. and Jay Lynn, S. (2012). Fragmented sleep, fragmented mind: the role of sleep in dissociative symptoms. Perspective. Sci. 7, 159-175. doi: 10.1177/1745691612437597 ← van Heugten – van der Kloet, D., Cosgrave, J., Merckelbach, H., Haines, R., Golodetz, S., and Jay Lynn, S. (2015). Imagineing the impossible before breakfast: the relationship between creativity, dissociation and sleep. Frontal. Psychol. 6:324. doi: 10.3389/fpsychg.2015.00324 Silence van Heugten – van der Kloet, D., Hutjens, R., Giesbrecht, T., and Merckelbach, H. (2014a). Self-reported sleep disorders in patients with dissociative identity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder and how they relate to cognitive failures and fantasy proneity. Front. Psychiatry 5:19. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014,00019 TENED TO van Heugten – van der Kloet, D., Merckelbach, H., Giesbrecht, T., and Boers, N. (2014b). Night experiences and daytime dissociation: a study of career analysis modeling. Psychol. Res. 216, 236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.053 ANTERVIATE TRY Vermetten, E., and Spiegel, D. (2014). Trauma and dissociation: implications for border personality disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 16, 434-444. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0434-438 Silence Waldo, T. G., and Merritt, R. D. (2000). Fantasy proneity, dissociation and symptomatology DSM-IV Axis II. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109, 555–558. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.555 Silence in life Wamsley, E., Donjacour, C., Scammell, T. E., Lammers, G. J., and Stickgold, R. (2014). Delicious confusion of dreaming and reality in narcolepsy. Sleep 37, 419–422. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3428 Quiet viv Watson, S. Chilton, R., Fairchild, H., and Whewell, P. (2006). Association between childhood trauma and dissociation between patients with border personality disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 40, 478–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01825.x Silence Wenzel, A., Chapman, J. E., Newman, F. C., Beck, A. T., and Brown, G. K. (2006). Hypothetized mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for border personality disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 62, 503–516. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20244 ← Zanarini, M. C., Ruser, T., Frankenburg, F. R., and Hennen, J. (2000). Dissociative experiences of border patients. Compr. Psychiatry. 41, 223–227. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90051-8 Silencio Palabras clave: confusion of sleep reality, border personality disorder, sleep disturbances, dissociation, cognitive disturbances, sleep content, limits Cytation: Skrzypińska D and Szmigielska B (2015) The confusion of sleep reality in border personality disorder: a theoretical analysis. Psychol 6:1393. Received: 19 April 2015; Accepted: 01 September 2015;Published: 15 September 2015. Edited by:Reviewed by:Copyright © 2015 Skrzypińska and Szmigielska. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the . It is permitted to use, distribute or reproduce in other forums, provided that the author or the original licensor is credited and that the original publication is cited in this journal, in accordance with the accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction that does not comply with these terms is permitted.* Correspondence: Barbara Szmigielska, Unit of Sleep Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University, ul. Ingardena 6, 30-060 Krakow, Poland, upszmigi@if.uj.edu.pl

Warning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. confusion of sleep realities in border personality disorder: a theoretical analysis Summary This document presents an analysis of the confusion between sleep and reality (DRC) in relation to the characteristics of border personality disorder (BPD), based on research findings and theoretical considerations. It is hypothesized that people with BPD are more likely to experience DRC compared to non-clinical people. Several variables related to this hypothesis were identified through a theoretical analysis of scientific literature. Sleep disorders: sleep problems are 15–95.5% of people with BPD (), and unstable sleep and candle cycles, which occur in BPD (), are linked to DRC. Dissociation: almost two thirds of people with BPD experience dissociative symptoms () and dissociative symptoms are correlated with a fantasy proneity; both dissociative symptoms and fantasy proneity are related to DRC (). Negative sleep content: People with BPD have nightmares more often than other people (); dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality tend to be more realistic and unpleasant, and are reflected in awakening behavior (). Cognitive disorders: Many patients with BPD experience various cognitive disorders, including problems with reality tests (; ), which can encourage DRC. Thick Limits: People with thin limits are more prone to DRC than people with thick limits, and people with BPD tend to have thin limits (). The theoretical analysis on the basis of these findings suggests that people suffering from BPD can be more susceptible to confusing the content of dreams with real awakening events. IntroductionConfusion in the reality of sleep (DRC) is a difficulty or inability to determine whether an event or experience occurred during the awakening state or whether it was part of a dream. Although only a few studies have been conducted on DRC in non-clinical populations (e.g. ; ; ), DRC has been investigated in specific groups, including narcolepsy patients (). Research has found that there is a relationship between DRC and psychotic symptoms (e.g., ), but the authors of this document have been unable to find any scientific study on the relationship between DRC and border personality disorder (BPD). The BPD is a generalized pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and affection, and a marked impulsivity that begins with early adulthood and is present in various contexts (DSM-V; , p. 663). To qualify for this diagnosis, the person should, among other symptoms, make a frenetic effort to avoid actual or imaginary abandonment, experience a chronic sense of vacuum or symptoms of temporary paranoid related to stress, or present severe dissociative symptoms. Moreover, persons with BPD often engage in self-destructive behaviours and are at significant risk of suicide. The border personality disorder affects between 1 and 5.9% of the general population (; ). Due to the complex psychopathology of the PB, many studies have examined different areas of operation in individuals with this disorder. This theoretical analysis addresses the question of whether individuals with certain features of BPD may have difficulty distinguishing between dreams and reality. The objective of this document is to provide an overview of the current knowledge of the Democratic Republic of the Congo regarding the characteristics of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. We hypothesize that BPD subjects are very predisposed to experiencing the DRC. This hypothesis is supported by the underlying assumption that there are groups of interrelated variables that are present both in the DRC and in the BPD. These variables, which we identify through an analysis of scientific literature, can be divided into the following categories: (i) sleep disturbances; (ii) dissociative symptoms; (iii) negative sleep content; (iv) cognitive disturbances; and (v) thin limits. This division was carried out on the basis of theoretical considerations; factors analysis has not yet been carried out. Each of these five variables is presented separately below. Variables present in BPD and DRCSleep disorders Sleep disturbances, for the purpose of this theoretical analysis, include a variety of sleep problems discussed below. Such sleep problems are very common among individuals with BPD (). Although there are few epidemiological data on sleep disorders among people diagnosed with BPD, cross-sectional studies show that sleep disorders prevail in 15–95.5% of this group (e.g., ; ; ; ).Compared to a non-clinical group, individuals with BPD take more time to sleep, sleep for shorter periods, have less sleep efficiency, and have frequent sleep disturbances (). The EEG recordings showed, for example, that participants in a BPD group, compared to a non-clinical population, had shorter sleep stages of NREM 2 and 4 and longer NREM sleep stage 1, and had high voltage delta waves during NREM sleep (; ). The REM dream was also different between groups, with BPD patients spending more time in the REM sleep, which had a longer latency, a first longer episode, and a greater REM density, as well as theta high voltage can and theta waves in the REM sleep, in participants with BPD (; ). Patients with BPD also have more nocturnal awakenings than people of a non-clinical population (; ). Frequent awakenings may cause difficulty in determining whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or was part of the sleep content (). Labile sleep cycles are another example of sleep disorders. They may occur in the course of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Police Directorate and are correlated with the Human Rights Commission (RC). Protracted sleep cycles can promote the intrusion of dreamed experiences in raising awareness that can lead to DRC and foster the feeling of depersonalization, which is a dissociative symptom. They also have an adverse effect on memory, thus favoring the creation of false memories (). Individuals who denounce sleep disorders mark high in dissociative scales, fantasy proneity (a tendency to deep and long-standing participation in fantasy and imagination; , p. 35) and are prone to false memories (). Together, previous relationships seem to support our hypothesis that BPD patients will likely experience DRC. It is suggested that a wide range of sleep disorders, such as labile-cloth sleep cycles, increase the tendency to experience nocturnal awakenings or nightmares (which are discussed in the "negative sleep content" section) in patients with BPD, which increases the likelihood that such people have problems distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or was part of sleep content. Dissociative symptoms Dissociation describes a state of disturbance and/or discontinuity in the integrated psychological functioning, such as consciousness, memory, identity or perception (DSM-V; ). Dissociative symptoms include derealization – the impression that the surrounding world or reality have changed, depersonalization – feeling as if one is an external observer of one's own self, and amnesia – an inability to remember, store and/or evoke memories. Dissociative states are experienced by approximately 2/3 of patients with BPD (). People diagnosed with BPD have a stronger tendency towards dissociative symptoms than the non-clinical population and individuals suffering from depression or schizophrenia (). The appearance of dissociative symptoms during the course of the BPD may be associated with child traumatic events. According to one of the theories of the etiology of the BPD, this personality disorder develops in individuals who report that traumatic events were a characteristic of their early life, mainly physical abuse and emotional abandonment. A study of 139 patients with BPD found that those who had high scores in the Scale of Dissociative Experiences (DES), which measures the frequency of dissociative symptoms, such as autobiographic amnesia, derealization, depersonalization, absorption and alteration of identity (), experienced significantly more severe emotional and physical abandonment and emotional and physical abuse (but not sexual abuse) during childhood than those who had low scores). Results suggest that people exposed to severe traumatic events during childhood are more likely to develop dissociative symptoms. Traumatic experiences can contribute to the development of dissociative symptoms because trauma-related stress leads to a sudden discontinuity of the individual's experience, as it awakes fear of security and disrupts the connection between the inner and outer environment. Traumatic experiences also often interfere with the integration of mental functions, leading to their dysfunction (). In addition, dissociative symptoms involve automatic avoidance strategies that defend the consciousness of traumatic memories (). It should be noted that dissociative symptoms are one of the correlates of the DRC (). , p. 157) noted that derealization is a commitment between dreaming and awakening. It seems that frequent experiences of dissociative symptoms or their intensification can cause frequent intrusions of dreams in experiences during the state of vigil. Dissociative symptoms and the proneity of fantasy – features linked to DRC – are correlated, and it seems that this correlation can be mediated by experiences during sleep (). High-level students of fantasy-prone report more dissociative symptoms than their friends who mark low or medium in fantasy-proneness (; ). In addition, individuals who find it difficult to discriminate between dreams and higher score reality in scales that measure dissociative symptoms and fantasy proneity that individuals who do not confuse sleep content with experiences during the awakening state (). A study of 51 women in the general population found that the proneity of fantasy is linked to both dissociative symptoms and daily cognitive failures (). In addition, dissociative symptoms, fantasy proneity, cognitive failures and sleep disturbances are correlated (). Later in this document, we present data that indicate that the disturbances in cognitive functioning are among the variables that increase proneity towards the DRC. The relationship between dissociative symptoms and the proneity of fantasy has also been observed in clinical populations. It demonstrated such relationships in groups of subjects diagnosed with BPD, schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. In addition, it was found that dissociative symptoms related to impulsivity in people with the BPD. This association is interesting because impulsivity is one of the diagnostic characteristics of BPD (DSM-V, ).In short, the previous findings support our hypothesis that people with BPD diagnosis are more likely to experience DRC because of their tendency to experience dissociative symptoms and related phenomena, such as fantasy proneity, sleep disturbances and cognitive problems. Negative Dream Content Individuals suffering from BPD experience more negative life events than other individuals, even those with other personality disorders (). According to the classical continuity hypothesis (; ), dreaming reflects the dreamer's life experience, therefore the dream content of patients with BPD can be more negative than other people's dream content. The quantitative analysis of a group of 27 people diagnosed with BPD and a non-clinical group of 20 individuals showed that the BPD group had dreams with more negative impact than those of the non-clinical group. Generally, people who suffer from BPD experience negative dreams, including nightmares, more often than people who have none of the symptoms characteristic of this personality disorder (). Nightmares are sleep disorders related to sleep disorders. They are defined as living dreams, loaded with negative emotions that awaken the dreamer of sleep (DSM-V; ). About 49% of patients with DB are affected by nightmares, while the prevalence of nightmares in the non-clinical population is estimated to be about 4–10% (; ). The increased frequency of nightmares among BPD patients compared to the non-clinical population is related to increased emotional instability and increased neuroticism in this clinical group (). The intensity of BPD symptoms is positively correlated with the frequency of nightmares (). To try to explain the prevalence of nightmares in people with BPD, we present two theories: a model of nightmare proposed by , and the model of emotional cascade developed by . proposed a theory to explain the occurrence of dysphoric dreaming, which is based on two main assumptions: the continuity between states and the multilevel explanation. The first, interstate continuity, supposes that some structures and processes involved in the production of nightmares are also dedicated during the expression of pathological signs and symptoms such as dissociative symptoms during the awakening state (p. 495). The second, the multilevel explanation, refers to the idea that the formation of nightmare can be explained in two different levels: the cognitive-emotional level and the neuronal level. At the cognitive-emotional level, there are imaging processes that represent emotional sleep images, while the neuronal level contains a network of brain regions responsible for imagistic and emotional processes. This model was created to explain the occurrence of nightmares in the course of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); however, it can also be used in an attempt to describe experiences related to both nightmares and interstate continuity in patients diagnosed with BPD. We will not discuss the concept of neuronal correlations of the DRC and the DB, as this is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we will focus on the notion of interstate continuity with reference to the BPD. In its model, consider a number of factors that underlie the continuity of the state, such as the burden – a factor of the state is the combined influence of stressful and emotionally negative events on the ability of an individual to effectively regulate emotions (p. 497), and affect the anguish – a trait factor is a long-standing trend and willingness to experience greater anguish and negative effect, and react with extreme behavioral expressions (p. 498). Other factors include high degrees of physiological and psychological reactivity, maladaptive coping, fantasy proneity, vividness of images and thin limits. Numerous studies suggest that almost all of these factors are usually present during the BPD course, but more recent studies indicate that there is no physiological reactivity intensified in BPD (e.g. ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). People diagnosed with this personality disorder are characterized by emotional disregulation, which is the inability to respond and manage emotions flexibly, which involves emotional sensitivity, high regulation and lay regulation. In addition, the BPD implies affective instability and a low level of recognition of emotions (). According to the biosocial theory, which explains the etiology of the BPD, this personality disorder develops in children (i) who have a biological propensity to experience negative effects, and (ii) who are in an invalid and toxic social environment. In the BPD, the biological sensitivity to emotional stimuli, the greatest negative effect, and a slow return to the emotional base are connected with difficulty to discriminate and label the emotional states themselves, starting appropriate strategies to manage these emotional states and being able to reduce intense negative affective states. Studies confirm that BPD patients show a negative distortion in identifying their own emotional states and emotional states of others (e.g., ). The inability to accurately recognize emotional states can intensify negative effects, emotional instability and emotional reactivity in everyday life. In addition, patients with BPD cannot tolerate discomfort and often use maladaptive regulation strategies to cope with the distress and negative emotions they experience, such as resections, impulsive behaviors or cognitive avoidance (). Emotional process disorders in patients with BPD seem to occur not only in the state of vigil, but also during sleep, as in the case of nightmares (). We hypothesize that astonishment and dreaming states may involve similar experiences; therefore, people with BPD may have difficulty discriminating if an event/experience occurred during the state of astonishment or was part of the dream content. Emotional disregulation, which is one of the factors associated with nightmares in theory, is also mentioned in its model of emotional cascade (ECM). The NDE tries to explain the etiology of the bad dreams experienced during the BPD. The effects of nightmares and other bad dreams, in addition to the fear they produce, can involve deficits in appropriate emotional regulation skills and diminish the ability to face the anguish during the next day, according to the NDE. Patients with BPD experience emotional cascades during the wave state, and this negative effect induces rumination – repetitive thoughts with mainly negative content. Ruminations increase the negative effect, which in turn intensify the rumins. These processes cause increased cognitive activity during sleep that favors the emergence of nightmares and maladaptive behaviors during the state of vigil that are intended to cope with negative emotions. It seems that frequent nightmares in people with BPD can influence the occurrence of negative life events (). Generally, a simplified model of emotional cascades assumes the successive occurrence of: negative emotional experiences during the awakening → increase of the rumins → increase of negative emotions → increase of the rumins → a very aversive emotional state → / possible dysfunctional coping skills connected with impact regulation (e.g., auto-chain, use of substances) / → high cognitive activity during the negative sleep cascades during the nightmare ) High cognitive excitation during sleep can cause awakening or semi-awakening, which can therefore lead to difficulty distinguishing between dreaming and awakening experiences (; ). In addition, the inability to effectively address stressful situations can increase the trend towards dissociative states (), which can eventually lead to a higher probability of DRC. In addition, a proven study that dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality are realistic, impregnated with negative impact, and give rise to behaviors in the state of awakening. However, because patients with BPD have more negative experiences both in the state of waste and in the state of sleep and more cognitive disturbances, they may have more difficulty recognizing whether an event/experience occurred during the state of awakening or was part of a dream. Overall, findings suggest that frequent unpleasant sleep content in the BPD can be a factor that increases proneness to the DRC. Cognitive Disturbing Patients with BPD may experience a number of different cognitive alterations. These include problems with metacognitive monitoring, which refers to the ability to observe one's own thinking processes, as well as to detect errors in its own reasoning, and inconsistencies in its own narratives. Metacognitive monitoring refers to "thinking in thought." Metacognitive knowledge, which is the ability to notice that some things/events may not be as they seem to be, is also distorted in the BPD (). Executive functions, such as working memory and inhibition of response, are usually also disrupted in the BPD (). On the other hand, the BPD is characterized by deficits in the processing of feedback, alteration of social inference and poor decision-making skills (; ). Generally, four types of cognitive disturbances are distinguished in the BPD: (i) transient, quasi-psychotic cognition, (ii) dissociation, (iii) social cognitive biases, and (iv) neurocognition). However, a detailed description of cognitive problems in the BPD is beyond the scope of this document. What is important is that problems with the evidence of reality can occur in patients with BPD (). The monitoring of reality, which is related to the testing of reality, seems to play a significant role in the process of distinguishing the content of dreams from awakening experiences. Monitoring of reality, a type of monitoring of sources, is defined as the ability to discriminate between memories of real events, and memories of dream events, imagination or delusions. The monitoring of reality consists of two decision-making processes: (i) evaluation of whether the characteristics of a memory stroke are more typical of memories of external events or memories generated internally; and (ii) evaluation based on current memory/knowledge, which is a more complex process and takes longer. The source of memory is distinguished on the basis of its characteristics: memories of actual events include more perceptual and contextual details, while memories of consciously imagined events include traces of cognitive operations that were involved in their creation. Dreams are classified as internally generated events, which are difficult to distinguish from external similar events because they are created without conscious cognitive operations (). In the case of dreams, conscious cognition, which is the most important point that would help to differentiate between memories generated internally and those generated externally is not present. These findings indicate that the DRC may be associated with difficulties with the monitoring of reality. The temporary suspension of the source monitoring process, together with the reduced capacity to respond to a sensory stimulus and reduced attention, is one of the common features of both dreaming and awakening fantasy. These processes can make it more difficult to distinguish between the content generated during sleep and the fantasy of awakening. Both the fantasy of awakening and the dreams play an integral role in the regulation of mood, the processing of adaptive information and the maintenance of self-cohesion by providing work templates for the future behavior directed by objectives and the development and maintenance of self-school (). BPD patients exhibit certain cognitive disorders that make them more prone to problems related to the tests of reality, and awakening fantasy can also disrupt the processes involved in correct monitoring of sources. In addition, it seems that mood regulation is disrupted in BPD due to a more negative sleep content and emotional cascades at night (). Cognitive and emotional processes during dreaming and awakening interact, and their interaction can contribute to the difficulty of distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the state of awakening or a dream. In addition, people who are more likely to make cognitive mistakes are less likely to rely on their cognitive skills (); therefore, they may be more sensitive to other people's suggestions. We hypothesize that people with BPD who have some cognitive deficits will rely less on their cognitive processes because they are not sure if their perception of reality is correct. Our assumption is that due to their cognitive disturbances, people with BPD, compared to non-clinical populations, will most often not be sure what the source of certain events or experiences (see v. reality), and may even do incorrect judgments about their source. The difficulty that BPD patients encounter in the test of reality () and their problems with metacognitive monitoring and metacognitive knowledge () appear to be the only examples of cognitive disturbances that could lead to a greater probability of experiencing DRC, compared to people of non-clinical populations. Thin Boundaries The concept of limits, which was defined by , refers to a wide spectrum of limits in the mind, including the interpersonal limits (self vs. others), the limits between the self and the outside world, and the limits between different states of consciousness (e.g., the awake state or dream state). Therefore, the limits refer to: (i) the connection between various aspects of the mind (i.e., the relationships between thoughts, emotions and memory), including the relationships between the personal past, the future and the present; and (ii) the connection between the self and the outside world (). People have been characterized by thin or thick limits (; ). Since the limits are generally stable through situations, there is a high probability that individuals with thin limits in certain areas have thin limits in other areas (). Patients with BPD tend to have thin limits (), and individuals with thin limits have greater sleep memory than those with thick limits. They also experience more emotions in their dreams, have more negative and emotionally intense dreams, dream more often of verbal interactions with others, and consider their most significant and creative dreams (). A memory of higher sleep and other vivid experiences of the night are associated with a greater tendency to absorption, which is a state of greater imaginative participation in which an individual's attention abilities focus on behavioral domain, often the exclusion of explicit information processing in other domains and fantasize (p. 203). showed that absorption is correlated with greater creativity, a tendency towards dissociation and greater involvement in activities based on imagination, with concomitant alterations in consciousness (). In this context, it may be interesting to ask questions about whether a greater ability to remember dreams increases the likelihood that sleep content is confused with real events. As patients with BPD have a higher tendency to absorb (), they would experience the DRC more often, perhaps in relation to other variables discussed in this document. The thick limits seem to improve the intrusion of dream content in the consciousness in the wave state, which can lead to difficulty distinguishing whether an event/experience occurred during the awakening state or in a dream (). In addition, these intrusions may favor the emergence of dissociative symptoms, which, as mentioned above, are correlated with the DRC (; ). These data suggest that individuals with fine limits can be more prone to DRC. Therefore, patients diagnosed with BPD may also be more likely to be more likely to DRC. Taking into account the above considerations, it would be interesting to undertake studies on the relationship between creativity and DRC in BPD populations and non-clinical populations. Although a recent study found a moderate correlation between state dissociation and creativity, there was no significant correlation between creativity and unusual sleep experiences. Future studies should include the DRC as a construct to clarify its relationship with creativity. Conclusions The above paragraphs describe the variables that can lead to a greater tendency to experience DRC in DBPD patients. Taking into account everything, we propose a tentative model that patients with BPD are more likely than the non-clinical population to experience difficulties or an inability to determine whether an event or experience occurred during the state of vigil or was part of a dream. Patients with diagnosed DB may be more likely to experience dissociative symptoms due to traumatic events in their early childhood (), and dissociative symptoms are DRC correlates (). Thus, the greatest trend towards dissociative symptoms among people with BPD can make them uncertain if something they remember happened in their dreams or while they were awake. Dissociative symptoms are correlated with the proneity of fantasy, which is also correlated with DRC (; ; ). In addition, people with BPD often suffer from various sleep disorders (), and sleep disorders (e.g. nightmares) and unusual sleep experiences are related to dissociative symptoms and DRC (; ). In addition, patients with BPD experience negative emotions during awakening that are related to negative emotional experiences during sleep (). This process can also be connected to the high cognitive excitation during the dream that causes awakening or semi-awakening, which leads to the difficulty of distinguishing between dream experiences and awakening (; ). Furthermore, dreams that are more likely to be confused with reality are realistic, evoke negative emotions, and give rise to behaviors in the state of awakening (). The sleep content of patients with BPD is more negative than the sleep content of individuals in non-clinical populations, and people with BPD tend to experience a number of different cognitive alterations, such as problems with reality tests, metacognitive deficits, disruption of social inference, poor decision-making skills or cognitive distortions (; ; ; ; ; ; ). In addition, people with BPD are characterized by thin limits (), which can further improve confusion between dreams and awakening. This theoretical analysis, including variables such as sleep disorders, dissociative symptoms, negative sleep content, cognitive dysfunction and thin limits leads to the proposition that patients with BPD can be more prone to DRC, compared to non-clinical population. Future research on the general working model should involve the use of factor analysis and structural equation modeling to identify and confirm important variables and explore the complex relationships between these variables. We plan to conduct an empirical verification of these relationships. The aim of this comprehensive research program is not only to examine whether patients with BPD are more vulnerable than others to experiencing DRC, but to study in a comprehensive way the psychological and neuropsychological aspects of sleep and dreams, using subjective methods and objectives, in a continuum: BPD – some features of BPD – lack of BPD. The theoretical analysis presented above is exploratory in nature and aims to serve as a starting point for more advanced analysis, and to provide a theoretical basis for the planning of empirical studies. Conflict of interest The authors state that the investigation was conducted in the absence of commercial or financial relations that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Can lucid dreaming mess with reality? Can someone become confused as to what is reality and what is a dream? - Quora

Narcoleptics Can Have a Hard Time Telling Dreams From Reality/expectation-vs-reality-trap-4570968_FINAL-23dcc111010b4d72b43aec09f0bbd9a3.png)

The Stress of Your Expectations vs. Reality

Dreams that feel real

Slow Sleep – the blog of sleep: Confusing dream with reality. Has it ever happened to you?

Dreams or Reality….? | Which me am I today?

Not Sure If Reality Or Realistic Dream by ninjainpyjama - Meme Center

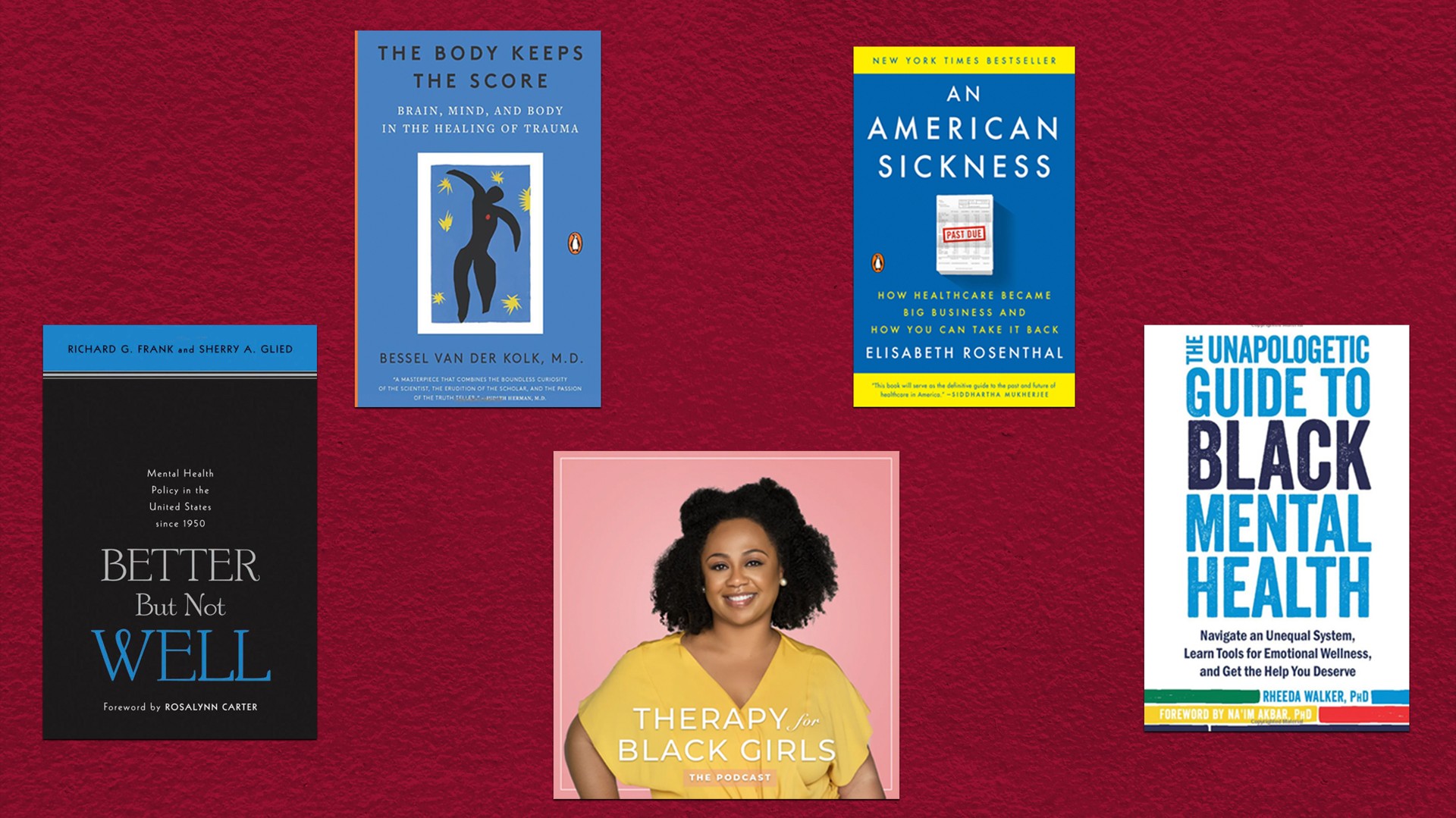

PDF) Dream-reality confusion in Borderline Personality Disorder: A theoretical analysis

I Confuse Dreams with Reality | Am I Sleeping Now? - YouTube

28 Life-Changing Quotes on Dreams and Reality | It's All You Boo

45 Facts About Dreams: Sex Dreams, Nightmares, Fun Info, and More![Stephen LaBerge Quote:]()

Stephen LaBerge Quote: "If the experience of reality matters, than nothing is going to be better than dreaming. Because dreams feel real to ever..." (7 wallpapers) - Quotefancy

What dreams may come: why you're having more vivid dreams during the pandemic

The Nature of Lucid Dreams Although lucidity is usually accessed through normal dreaming, do not confuse lucid dreams … | Lucid dreaming, Vivid dreams, Book show

5 Mind-Bending Facts About Dreams | Lucid Dreams & Nightmares | Live Science

Pin on Story of My Life :)

Dream - Wikipedia

The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Changing Our Dreams - Scientific American

8 Dream Signs You Shouldn't Ignore

The Benefits and Risks of Lucid Dreaming

Dreams About Being Pregnant: 6 Dream Scenarios and Interpretations

6 Vivid Dreams that Seem Even More Realistic than Real Life | Slism

Realigning Your Expectations: Dreams vs Reality

Melatonin Dreams: Does Melatonin Cause Vivid Dreams?

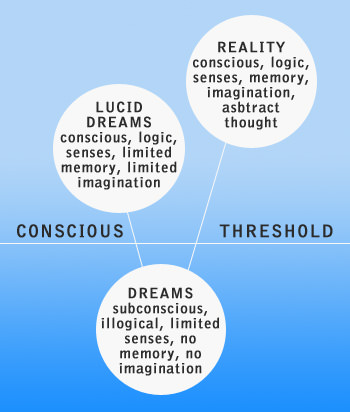

Lucid dream - Wikipedia

Dreaming, Philosophy of | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy![🐥리사+ROSÉ 3.12 on Twitter:]()

🐥리사+ROSÉ 3.12 on Twitter: "As promised, here's the replies of Jisoo talking about Lucid Dreams. Idk how they end up talking about it. Btw its rough trans so bear w/ me… https://t.co/EuJtYAgtfA"

Is it normal to confuse dreams with reality? - Quora

Do Dreams Really Reveal Our Deepest Secrets? | Live Science

False Awakening: Meaning, Causes, When to Worry

Why Don't I Dream? Or Do I Forget My Dreams?

Is it normal to confuse dreams with reality? - Quora

Vivid dreams and their role in waking life - WHYY

Narcoleptics Can Have a Hard Time Telling Dreams From Reality

Why do our dreams feel so real?

28 Life-Changing Quotes on Dreams and Reality | It's All You Boo

Dreams that feel real

Narcoleptics Can Have a Hard Time Telling Dreams From Reality

19 Reasons To Ignore Everybody And Follow Your Dreams

Can You Confuse Lucid Dreams with Reality?

Can You Confuse Lucid Dreams with Reality?

/expectation-vs-reality-trap-4570968_FINAL-23dcc111010b4d72b43aec09f0bbd9a3.png)

Posting Komentar untuk "realistic dreams confused with reality"